I was seated at a wobbly table inside MartAnne’s Café, that unholy temple of green chile and punk rock, watching the steam rise off my plate of huevos rancheros like it might show me the future. James ‘Q’ Martin who goes by his middle name, a filmmaker, friend, and part-time Don Juan, sat across from me, sipping black coffee like it was penance. It was before I had my son, before the world got sharp around the edges, and I still lived in LA, where weather was optional and danger usually came with a warning label. This is what these trips were about, getting a bit uncomfortable.

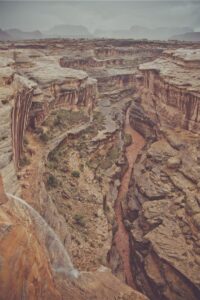

Q introduced me to Justin Clifton. Baby faced. Born and bred Flagstaff, two, maybe three generations deep. He had that desert look: lean, quiet, observant. Still optimistic, like he hadn’t seen the best parts of himself worn away yet. He said he was an aspiring filmmaker. Justin packed a duffle without hesitation. No questions, no flinch. That told me Q had vetted him. That told me I didn’t need to. The mission was simple in theory: cross the Navajo Nation, climb over Cedar Mesa, and descend into Edward Abbey country — the Maze District of Canyonlands National Park. A route cobbled together from memory and myth. A missing link to my Utah Traverse. A landscape that didn’t care about names or credentials.

We loaded into my ‘99 Land Rover Discovery SD — built like a Cold War escape plan. Front and rear lockers. Winch. Overbuilt suspension. It looked like it belonged in a far-off country working for an NGO or a magazine, depending on the angle. I trusted it more than I trusted most people. Justin talked as we drove — stories about delivering compressed air and acetylene across the The Navajo Nation for his dad’s company, hauling volatile gases over forgotten highways like it was a summer job. I half-listened, scanning the sky. The wind picked up around Kayenta, dragging sand across the asphalt. A curtain of cloud, thick, bruised, biblical, built along the western horizon. I told myself we’d outrun it. That was the LA in me. Arrogant. Naive. I needed a reality check.

We reached White Canyon just after dark. Pulled onto a sandstone ledge slick with drizzle. Stretched the tarp, lit the stove, warmed soup at the rear hatch. We pitched our tents to the sound of nylon snapping in the breeze. Rain tapped like code against the fly, a soft, wet lullaby.

The smell of the desert in rain is a resurrection. Sage, pinyon, and sandstone — a clay-born perfume that smells like the Earth bleeding out its secrets. Perfumers LeLabo or DS & Durga wish they could replicate it.

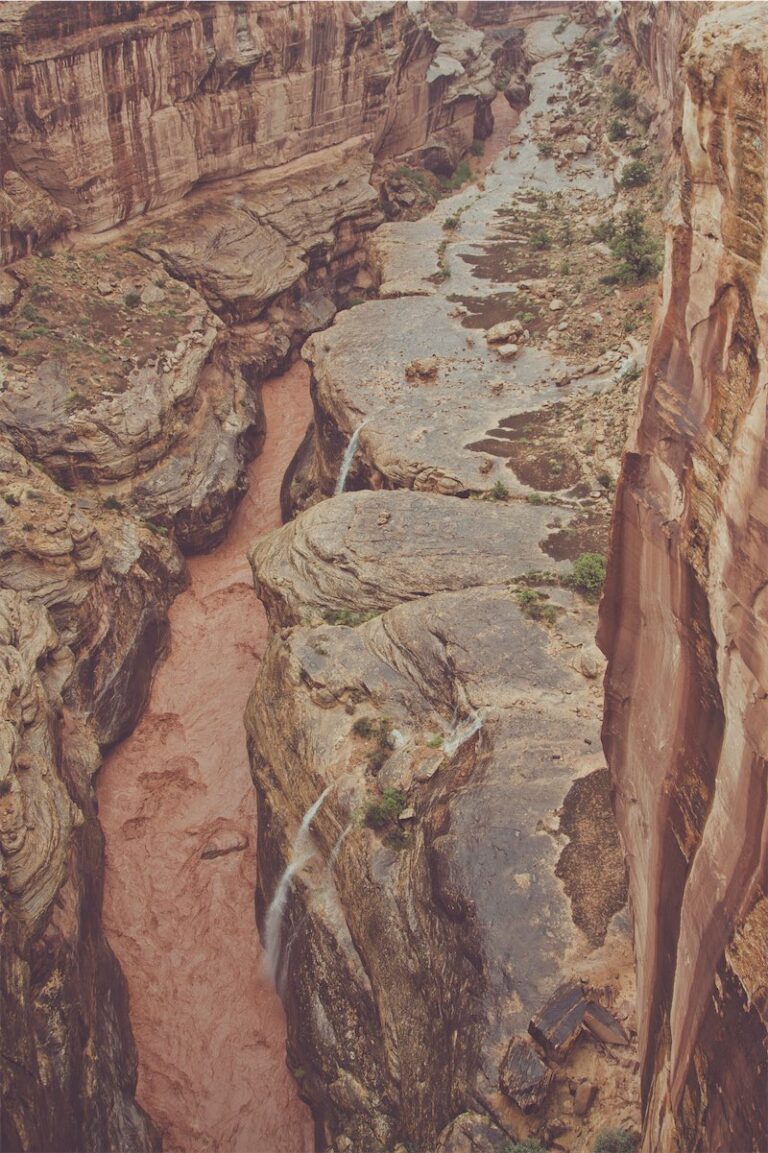

In the morning, after coffee and instant oatmeal cooked on a Jet Boil, we stopped at the White Canyon bridge. Thirty miles east the sky opened up and dumped everything it had. The drainage was flooding—chocolate water rushing toward the Colorado. The same dry canyon we’d crossed the day before was now a torrent. Time doesn’t exist out here the way it does in cities. Things change. Fas

We kept pushing. Crossed the Colorado River. Turned off the highway. From where we were, remote to say the least, by pavement it is 50 miles to the north to Hanksville or 75 miles to the south to Blanding. We were going 110 miles without any side detours north over dirt roads until we saw pavement again. At least the storm looked over. False calm. A ring of storm clouds hovered like sentries. I call that kind of calm a sucker hole because you’re a sucker if you think you’re in the clear.

Somewhere south of Gunsight Butte, we hit a wash. Brown water, cement-thick, flowing fast. I killed the stereo. Flash floods aren’t theater. They’re the desert’s ambush predators. Craig Childs said it best: “There are two ways to die out here; thirst, and drowning.

We got out of the Rover. The rain was steady. Boulders clattered under the surface of the wash like bones in a drum. We didn’t even have to say it, of course we weren’t crossing. We backed the truck up past the high-water mark. Watched the flood rise. Dishwasher-sized rocks tumbling in the brown slurry, surfacing and crashing like whales. It was stunning. Apocalyptic. Beautiful. Then, like it had never happened, the water dropped. Rain pulled back. We moved on.

Canyon country is made of layers. Some handle water. Others, like bentonite — a clay-rich volcanic ash that swells when wet — turn slicker than grease on marble. From the base of the Orange Cliffs we had a climb — 1500 feet (about 457 meters) — up to the mesa.

The first two thousand feet were tame — sandy, reliable slickrock. But then came the clay, then the bentonite. Dry, the road’s uneventful. A casual climb to a sandstone bench below the Wingate. But wet? That bench turns treacherous. Bentonite becomes a trap, and tires lose grip, and trucks slide sideways. And to our right, a sheer drop. I dropped the Rover into 4-low, engaged the lockers front and rear. Hugged the uphill ditch, leaning the weight into the slope to keep from tipping into nothing. The cab was silent except for the engine and our breath. There’s no glory in a moment like that. No cinematic swell. You don’t rise to the occasion — you fall back on what you’ve rehearsed. Your training, your instincts, all the quiet repetition. The seat time. The miles. The hours spent in the dirt. That’s what shows up. Or doesn’t. Once we hit drier sandstone, the exposure let up. False summit.

Justin didn’t know the trail. I did. The true test lay ahead, the Flint Trail switchbacks. Narrow, steep, loose rock. A backcountry bootcamp for vehicles and nerves. My adrenaline from the bentonite layer crashed. Anxiety slipped in like fog through a crack.

We could’ve bailed. Headed west into the Maze proper. Flat, sandy, a known escape. But we didn’t have permits. And while permits are always secondary to survival, I used it as an excuse. Said we should at least “lay eyes on the switchbacks.”

We were already committed. And deep in Edward Abbey country now. The kind of place that erodes your edges. Makes you remember who you are, or who you once were before the world got loud. The clouds pressed down like wet cotton as we climbed through the pinyon-juniper forest. Visibility dropped. The cliffs above us — those massive, rust-colored sentinels — vanished into mist. It had been a few years since I’d driven this road, and the last time I’d come down it, descending into light. Now we were climbing into shadow. I tried to remember — were there three switchbacks? Five? Confidence was high. The road was holding, at least for now. Broken sandstone and red sand, spongy under tread but not yet betraying us. The first switchback — cutting left — felt like a warm-up. No drama. Then came the first real problem.

We pulled up short. A massive rut had split the roadbed like a fault line — right where the track curved uphill. We stepped out. The rain had excavated the mountainside, carving out the road’s interior and leaving only the bare bones of the route. But it was doable. If this was the worst of it, we’d be fine. But it wasn’t.

The next switchback — tight, curling right around a sandstone spire — climbed a series of ledges. In dry weather, they’d barely register. But today, water had gouged the driver’s side, eroding the roadbed, exposing buried boulders and the skeletal structure beneath. A little farther ahead, runoff poured down in thin crimson streams, twisting between rocks and roots, dragging debris into the ruts. Justin scouted ahead, walking slow, methodical, his hood pulled tight. I eased forward, one inch at a time.

The Discovery crawled like a machine bred for this moment — center diff locked, front and rear lockers engaged, low gear biting down. It felt planted, grounded in the kind of way that makes you feel superior to gravity. The body creaked as we rode the edge, aluminum skin occasionally pinged by tumbling pebbles — each hit like a reminder: you’re not in control here.

Small streams snaked down from unseen cliffs, carrying slurries of mud and time. Rocks, pebbles, fossils dislodged from ancient layers above. We weren’t just driving a trail — we were moving through geologic time in real time. Each sedimentary ripple, each broken ledge, was a mile marker on a timeline that didn’t care about us or our carefully prepared gear.

The bentonite was behind us. The cliff face eased. We reached the top — just like that — and pulled onto the plateau. The sky lightened, only slightly, as if offering a nod of respect.

Then she looked out the window, searching the empty lot.

“Where did you come from?” she asked

“Highway 95,” I said, still brushing red dirt from my sleeves. “Up the Flint Trail. Can we get an overnight permit for Panorama Point?”

She turned fully. “What do you mean you came up the Flint Trail?”

“Oh. Is it closed?”

She blinked. “No, it’s not closed. But we just got a record 3½ inches of rain in the last 24 hours.”

“Yeah, that tracks,” I said, scrolling through my camera. I showed her and her colleague a few photos. Flash floods, freshly cut ruts, Justin with that calm, wet look of someone not surprised anymore. They shook their heads. I couldn’t tell if it was admiration or disbelief.

Paperwork was paperwork. We signed it, got our permit, and headed out toward Panorama Point. The route was forgiving now, flat mesa country, open sky, a blend of soft sand and sprawling slickrock. The storm had passed, but the land was still soaked in it. Every puddle shimmered with rust and sky. The smell of juniper and wet stone clung to everything.

It was an incredible time to be in the Maze. The place felt untouched — not just by people, but by time itself. The air had that post-storm stillness, where everything’s been reset. No footprints, no tire tracks. Just the memory of water and the promise of silence. It was the perfect time to be there.

Because no one else was.