Living in New England during its winters assures you of bouts of “Skier’s Flu,” a condition caused by recent snowfalls and a desire to flee the workplace or home. While on the slopes recovering from this disease, I have heard ski instructors ridicule my skiing techniques, learned from my experiences, saying they would doom me to the bunny slopes if I didn’t change them.

The same holds true for my off-roading techniques, which many Land Rover Driving Team (Fred Monsees, Warren Blevins, Sean Gorman, Daphne Greene, Jamie Cote) and Land Rover Experience instructors (David Nunn, Gene Schubert, Matt Albritton) have sought to improve over the decades. As with every enthusiast, I want to believe that my off-roading talent (however slight) would put me in line for the next Defender Trophy — or the granddaddy of them all, the Camel Trophy.

Spending time inside and around the 1998 Camel Trophy Defender 110 Team Support vehicle at Pebble Beach [See Fall 2025 issue -ed.] brought back a flood of memories from the only wintertime Camel Trophy competition. Little did I know that a visit to the Land Rover Experience at the Quail Lodge in Carmel, CA, would immerse me in Camel Trophy dreams.

That’s where I saw the remarkable memorabilia collection of Brenton Corns, an LRE Instructor and founder of 4XFarAdventures. Tucked away inside his office were four Pelican cases, each filled with the most fascinating Camel Trophy artifacts. Brenton explained why he has searched worldwide for these items:

“Almost 15 years before buying my first Land Rover in 2007, I bought a pair of Camel Trophy boots. At that point I had never heard of the Camel Trophy, but the display imagery of that yellow Defender driving down the middle of a river made me want those boots.”

“Upon purchasing my first Discovery II in 2007, the Camel Trophy imagery came back, this time in forums and online galleries. I began to wonder, “How do you get 20 teams from around the world to participate in a near two-week adventure in the middle of the jungle?!” Little did I know, that simple question would lead me down a path of immense research and discovery.”

“One of the more stand-out memories of that research was finding an event jacket that was owned (and sold) by Chris Bennett. He’s the author and photographer from the UK who wrote a book on the 1994 Camel trophy. Chris and I started talking and I was able to acquire all of the rolls of unused photos that did not make it into the book. Being a photographer myself, holding this film got me a little closer to being on the event itself. Knowing that the photons of light had bounced off the participants (the Cameleers as Chris would call them), the vehicles, and desert surroundings and was then captured forever in that film cellulose now in my hand was pure joy!”

“I’m really excited to see the return of the modern iteration of the Camel trophy, the Defender Trophy! People have been clamoring for an event like this for decades, and the adventure in Africa next summer will be one for the record books and photo books!”

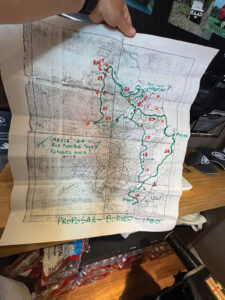

Maybe Howard Carter, the archaeologist who discovered King Tutankhamen’s tomb in Egypt, or Richard Leakey, the anthropologist who uncovered humanoid fossils in Africa, felt as I did when I touched the boots, unfolded the shirts, stared at the trail maps, and immersed myself in Brenton’s Camel Trophy cache.

Once back in Maine, I found a VHS tape of the Tierra del Fuego event and watched it with eyes wide open. That led me to revisit the 1998 event chapter in Nick Dimbleby’s Camel Trophy: The Definitive History (2021). He summarized the impact of the Tierra del Fuego competition.

1998 saw a change in the direction of the Camel Trophy competition. That year’s challenge would include the first winter event in a long-distance trek from Santiago, Chile to Ushuaia, Argentina. As Nick described it, “En route, teams visit ‘Adventure Locations’ and ‘Discovery Locations,’ experiencing the beautiful natural scenery on foot, behind the wheel of a Land Rover, on a mountain bike or in a kayak.”

Instead of traveling in convoy, each team would set off alone in a newly-launched Freelander as their vehicle, equipped with Garmin GPS and EPIRB homing beacons. A Defender 110 support vehicle, driven by previous years’ competitors, stocked with spare parts and carrying journalists, would accompany each team. The distance covered — over 5,000 miles — would comprise the longest Camel Trophy to date, likely in the most inclement weather.

The Tierra del Fuego Camel Trophy also introduced strategic navigation on the part of every team. Each Discovery Location required the team to determine the best routes that day, based on points assigned by degree of difficulty. Each day’s route required the team to select from a range of off-pavement drives and link with 140 different Adventure Locations. At that point, the team would receive instructions to kayak, mountain bike, ski, drive — or a combination of required activities. You could not start the day until 30 minutes prior to sunrise and you had to end the day 30 minutes after sunset; miss those parameters and you would accrue penalties.

At once, this competition featured the longest distance packed into a three-week time span. The Freelander, with its L-Series 96 bhp 2.0L turbo diesel, full-time 4WD, 5-speed manual, HDC [Hill Descent Control] and ETC [Electronic Traction Control], performed without any major breakdowns. On occasion, the lack of low range meant the Freelander in first gear would go too fast for conditions or require the driver to slow down so much as to stall the vehicle. The resultant clutch slippage required the teams to stop and let the clutch system cool down. Otherwise, the compliant independent suspension gave it the ability to tackle gravel roads or dirt tracks at higher speeds than the support Defender 110s.

Greg Thomas of the US Team wrote, “I was surprised at how well [it] handled. You could make really sharp turns and on the ice you would start to spin, but as soon as you let off on the gas, you’d have traction again.” We spoke with Michael Warren, who confirmed a terrifying moment that he recounted in the April 1999 issue of Four Wheeler – a skid on an ischemic surface about 30 meters above a lake.

“The tracks [in the snow] left a frightening story as we careened on two wheels. Greg regained control only three feet from the edge,” he noted.

The US Team of Greg Thomas, a multi-media designer and adventure racer from Santa Cruz, CA, and Dean Vergillo, a full-time father from Duvall, WA, won out of 350 competitors for the coveted spots in the Tom Collins-led national competition. In the Tierra del Fuego competition, Thomas and Vergillo climbed as high as 4th place, fell to 14th (out of 20), and finished in 11th place overall. Most impressively, Vergillo and Thomas received 3rd place in the coveted Team Spirit Award. In the end, the French team of Michael and Mark Challamel won the Camel Trophy, with South Africa’s Mark and John Collins took the Team Spirit Award. A special Land Rover Award went to Spain’s Patricia Molina and Emma Roca.

Freelancer Melanie Goldman, writing in Salon, summed up her experiences:

“Driving is an art. If you ask an experienced off-road driver…

He will tell you that highway driving bores him to tears. If you ask a back-seat journalist, she will tell that she prays every hour for a strip of paved road.”

“Every once in a while — like now — we end up on the highway. But most of our 10 hours a day in the car are spent tackling windy, bumpy, muddy roads. Yesterday, I found myself wrapping my arms around my head as a helmet to soften the blow when a bump in the road at 30 mph caused me to slam into the window or the roof of the car. At its worst, the ride’s bumps knock my ribs up into my throat. At its best, it’s a moderate vibration that makes my spine feel like a slinky caught under a jackhammer.”

“Dean Vergillo and Greg Thomas — the two members of the U.S. team with whom I’m bouncing through South America — are extremely competent drivers, but some of the muddy, rocky, icy roads scare me so much I just squeeze my eyes shut like I used to do on roller coasters and wait for it all to be over. We had another conversation this morning about rolling a car, and I learned that you have to end up back on four wheels to make it an official roll, as opposed to a top-heavy vehicle just falling over, where it lands on one of its sides or its roof. If you know you’re going to roll, Greg said, tuck your head in and keep your hands away from the roll bars. Ahhh, the comfort of being prepared.”

The 1998 Camel Trophy would be the last one with Land Rover’s participation. It would lead to Land Rover’s creation of adventure events, from the G4 Challenge to the dealer TReK competitions, and in 2026, the revival of the Defender Trophy. The legacy of the Camel Trophy lives on through Camel Trophy Clubs, Camel Trophy reunions and in the memories of Land Rover enthusiasts worldwide.

[Nick Dimbleby’s book is available through Rovers North. Adam Bettcher’s photography is available at www.bettcherphoto.com -ed.]

1998 LAND ROVER DEFENDER 110

CAMEL TROPHY TIERRA DEL FUEGO

This Land Rover Defender 110 (built January 14, 1998, Solihull) was displayed at the 2025 Pebble Beach Concours d’Elegance. It was used by the United States team of Dean Vergillo and Greg Thomas on the final Land Rover-based Camel Trophy in 1998. The teams were primarily using Land Rover Freelander, along with the Defender, to carry equipment and journalists. The event was a long 4800-kilometer (2982-mile) trek through the landscape of Tierra del Fuego, starting in Santiago, Chile, and concluding in Ushuaia, Argentina. This event, rather than having a set route, had over 200 checkpoints categorized as ‘Discovery’ and ‘Adventure’ on the event. The Discovery checkpoints used the Freelander kit, and the Adventure checkpoints used equipment carried in the Defender, such as skis, mountain bikes, and kayaks. This event was the final Camel Trophy that directly involved Land Rovers.

Camel Trophy 1998: The Results

Teams representing 20 countries competed in the ‘98 Camel Trophy. The teams collected points by reaching any combination of up to 225 destinations, with point values assessed according to difficulty. These included “Discovery Locations” (roadside points of interest) and “Adventure Locations” which required more challenging driving or the use of kayaks, skis, or mountain bikes. The final standings:

Team Points

- France 2,593

- South Africa 2,550

- United Kingdom 2,352

- Canary Islands 2,252

- Portugal 2,230

- Spain 2,215

- Germany 2,205

- Romania 2,126

- Russia 2,110

- Switzerland 2,093

- U.S. 2,049

- Greece 2,003

- Argentina 1,963

- Italy 1,814

- Austria 1,511

- Turkey 1,506

- Denmark/Norway 1,448

- Holland 1,445

- Japan 1,274

- Finland/Sweden 1,055

SPECIAL AWARDS:

- Andean Sports (skiing, et al): France

- Mountain Biking: Switzerland

- Driving: South Africa

- Land Rover Award (most checkpoints): Spain

- Kayaking: Italy

- Team Spirit: South Africa

1998 Land Rover Freelander I, L314

Engine: (Freelander) Four-cylinder 2.0 Litre turbo diesel L-series (1,994cc). 96bhp at 2,000rpm.

Drivetrain: Full-time 4WD. Five-speed manual transmission with no transfer gearbox. HDC (Hill Descent Control) and ETC (Electronic Traction Control).

Camel Trophy Kit:

- Front A-bar incorporating two driving lamps and the winch remote-control socket.

- Demountable Warn 5000SDP winch with 5,000 lb pull and 15 meters of cable. Stored in rear.

- Front-mounted galvanized steel steering guard.

- Dixon Bates heavy-duty towing eyes mounted onto the front A-bar.

- Full-length roof rack mounted directly through the roof onto the internal roll cage.

- Roof rack tonneau cover.

- Four front-mounted spot/flood lamps recessed into unique Camel Trophy light pod.

- Rear-mounted spot lamp.

- Front and rear lamp guards.

- Full internal roll cage.

- Electronic ‘Pacer’ tripmeter specially designed for Camel Trophy.

- Separate rear seats as fitted to three-door Freelander, leaves middle section clear for kit.

- Waterproof seat covers and rubber floor mats.

- Flexible map lamp mounted on the transmission tunnel.

- Rear compartment dog guard.

- Fire extinguisher.

- Tool kit.

- First-aid kit.

- VHF event radio.

- Satellite telephone.

- A pointed shovel.

- An assortment of tow ropes, all with hooks at either end.

- Hand spot lamp with 12-volt connector.

- Heavy-duty winch control.

- An airbag exhaust jack.

- A volcano kettle.

- Winch bag, including gloves, shackles, tree strop and pulley block.

- Satellite navigation equipment (GPS).

- EPIRB (Emergency Positioning Indicating Radio Beacon).