The “heritage” Land Rovers that most of us drive, from Series I’s to Range Rover Classis / P38-A’s, to Discovery I-LR3’s, don’t interest the Kardashians. Thus, these Land Rovers provide us with two bonuses: you can work on them yourself, and no Kardashians will be found in them.

This fall I found myself opening toolbox drawers on two different Series Land Rovers and calling Rovers North often. One Series II-A on this island qualifies as a “bitsa” titled as a ’64, it has a later II-A steering wheel, a ’68 II-A brake booster and a few pieces on the motor that defy identification. It rarely gets used as its owner lives in Texas and only occasionally drives it here. Also, the Rover really needs some substantial frame repair, so the owner is reluctant to spend much money on repairs.

Over time its clutch started to lose its effectiveness; the clutch pedal became softer and softer. For a couple of visits, I could make it work by bleeding it each time at the slave cylinder; in recent months, that would last only for a day. I also noted that clutch fluid looked quite coagulated and dark, not the handsome Vermont Grade A maple syrup color you expect to find in the reservoir.

Changing out the slave cylinder on a II-A can normally be done from underneath the car, but this one was mounted such that only removing the floor and the transmission tunnel allowed you to access the slave cylinder. Once accomplished, I found the pedal would still not firm up properly, and the owner agreed to let me change out the master cylinder. The Haynes Manual instructs you to first “remove the wing,” but instead, I removed the brake booster bolts and maneuvered it to one side as I pulled, tugged and yanked on the clutch pedal assembly to remove it from the bulkhead. Many curses later I finally freed it, so I could remove the cylinder and install the new one.

You should “bench bleed” (fill it with fluid and pump out the air) before reinstalling it, but having to move the pedal itself in order to reinstall it meant that it lost its prime and sucked in air. Pumping the pedal to bleed it accomplished nothing, but removing the hose to the slave cylinder and dipping the hose into a jar of fresh fluid let me bleed it as you would a brake master cylinder. A few pumps to bleed the slave cylinder screw and the clutch had its requisite pressure.

Not long after I had to turn my attention to the QE I, which cried out for deferred maintenance. When the left front directional stopped blinking, I wondered about the bulb. Removing the lens revealed a completely rusted out socket. One arrived the next day and it took only a few minutes to install. Next came a suspect fuel pump; on Rob Smith’s recommendation, a new one appeared on my doorstep. It’s hard to say why Land Rover hid the nuts on the studs underneath the pump, because you can’t reach them from below without removing the oil filter canister. So you lean over the wing, blindly operating the ratchet and wondering whether you’re loosening and tightening the correct nuts. The car did start right up, however. A leak at a rear wheel cylinder will have to wait; the parts have arrived, but I’ll postpone this repair until the rain stops and the ground dries this weekend. Meanwhile the QE I goes about its daily work with aplomb and a little more attention to stopping safely.

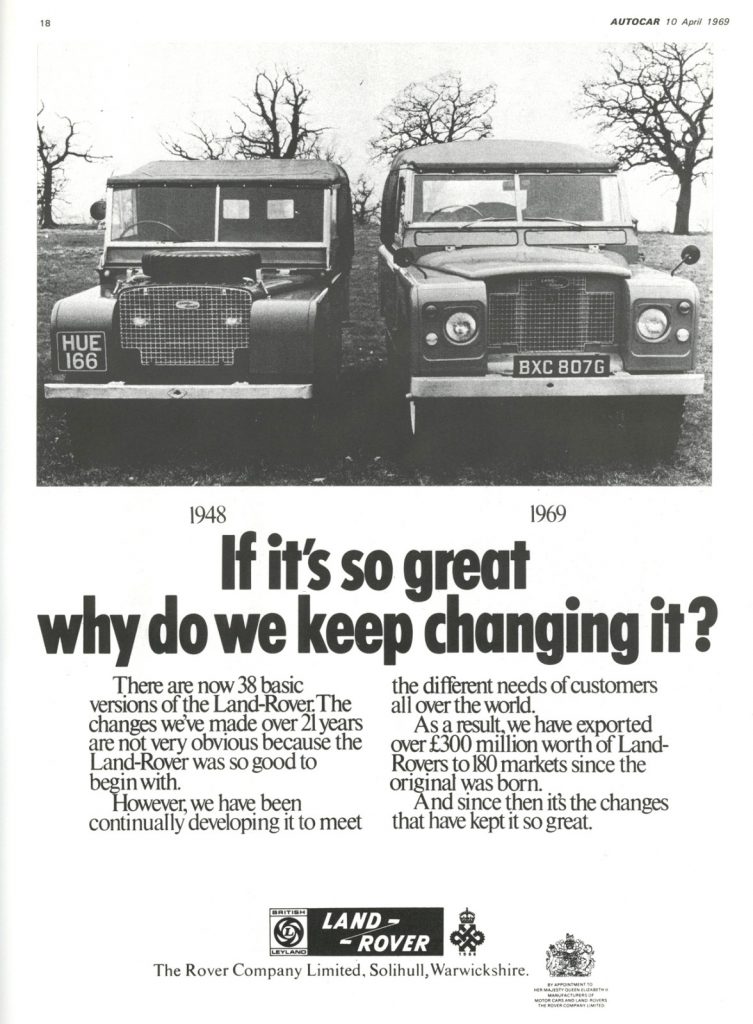

Back in 1969, a Land Rover advertisement wondered, “If it’s so great, why do we keep changing it?” The response was that “we have been continually developing it to meet the different needs of customers all over the world. As a result, we have exported to 180 markets since the original was born. And since then it’s the changes that have made it so great.” That text came from a time when the Series II-A was the only Land Rover; regardless of its wheelbase (88” or 109”), its body configurations or lighting and emissions gear for different markets, it was essentially the same vehicle.

That’s not a luxury that Land Rover has in today’s automotive world. Sometimes it can be hard for enthusiasts to remember that Land Rover is, after all, in the business of manufacturing and selling new vehicles. That marketplace has changed greatly in just the past 20 years; you need only think of the roster of automobile marques no longer manufactured to recognize this reality.Recently, I had the pleasure of being behind the steering wheel of newer Land Rovers, from those with sliding windows to those with electric windows, from manual tailgates with chains and clasps to those that open with a wiggle of a foot.

During its British Leyland, Rover Company Ltd. and Royal Warrant years of Series 88” and 109”’s, Land Rover advertised itself as a vehicle for “really tough assignments, like collecting the kids from school. And their friends. And their friends’ friends. The Land Rover can handle it. Comfortably. You can seat all-comers in soft-cushioned seats.” I’m looking at the seat squabs in the QE I, my ‘66 Series II-A, and wonder if we’re talking about the same seats. Yes, “A Land Rover can put in a hard day’s work winching down trees in a farm field… But then you see how useful it really is. When it takes the evening off and goes to the pictures.”

At this year’s Mid Atlantic Rally I got to ride around off-road in Bob Steele’s ‘95 Range Rover Classic—now there’s a vehicle in which to “go to the pictures.” Have you been in one recently? The “command seating position” is more than a marketing gimmick. You sit upright with a perfect view of the bonnet, sides and rear. Grab handles above your head help you hoist yourself up on the trails. Bob’s SWB fit the narrow, muddy, tree-lined trails perfectly; his skillful driving and occasional use of rear air lockers kept us from having to winch. The instrument binnacle atop the dashboard houses all the information needed in a perfect location for an unobtrusive view. The passenger cockpit might feel narrow in 2015, but the thin pillars and large greenhouse make the substantial vehicle seem light and airy. Oh, yes, and you can still maintain, repair and/or customize this Range Rover yourself. This last year of the Range Rover Classic proved that the 1970 engineering brief had it right from the start.

I’ve covered the joys of driving the new Range Rover and Range Rover Sport elsewhere in this issue. In October Land Rover Richmond provided me with a lightly-optioned 2015 Discovery Sport and I enjoyed 500 miles of highway, two lane road and off-road driving at the 2015 Mid Atlantic Rally. It’s the third time I’ve spent time in a Discovery Sport and I remain as enamored as ever. As Land Rover’s “entry level” model, it must also appeal to newcomers to the Land Rover brand, the sort who might turn to Consumer Reports for automobile tests. I don’t know what their testers were drinking when they dissed this newest Land Rover, but I would have volunteered to be their designated driver that day. They clearly could have used the help.

The Discovery Sport’s 9-speed transmission comes with two setting selections, “D” or “S.” You can guess what they mean. If you want to roll along, roll along, all the live-long day in traffic, “D” does just fine. If you need/want to move right along, you turn the gear knob to “S” and press down on the accelerator. The shift points change at the red line on the tach and you charge vigorously; happily, the Disco’s exhaust lets you hear the 2.0L turbocharged engine at work. When you want more relaxed cruising, you re- turn the knob to D. On the interstate, the Discovery turns 2,000 rpm at 70 mph for very relaxed cruising.

On two lane roads shift back to “S” and you enjoy fine handling on winding roads. I’m not basing this assessment against my Series II-A; I own and drive sports cars, and have been forced to rent enough contemporary vehicles to make a fair comparison. Incidentally, the handling holds whether I’m the only person in the Land Rover, or the other four enthusiasts and one Australian shepherd have piled into the 7-seater. Oh, and I can’t forget the grip in pouring rain, drizzle or dry roads—it felt the same no matter what the weather.

Off-road, the Discovery Sport, with its stock street tires, walked its way through the muddy, Virginia clay trails and slick grassy hillsides with only the slightest difficulty. As the Discovery II’s and Defenders with mud and snow tires powered and clawed their way up the same trails, I pushed the buttons for “Mud and Ruts” and “Hill Descent” and enjoyed how the Discovery Sport spurted its way up the same trails. It never became stuck on any ascents and the paddle shifter controls allowed you to set the hill descent to 5 mph for complete control. Only once did it refuse to move forward and that was on a slightly inclined field of mud in which nothing else moved, either. Reversing back a few times to find firm ground and engaging one set of wheels on that surface gave the car momentum and it continued apace. It received compliments from participants who did not anticipate it could perform that well in the challenging conditions.

This Discovery Sport had few options, which let me experience the Land Rover most enthusiasts prefer. I had to rely on my phone and a map for directions, but I certainly appreciated the heated seats after working in the rain for a few hours. The seats and interior coverings didn’t seem to mind the mud and dirt that filled it over the long weekend. Those two fold up jump seats in the rear appeared ok for compliant friends and access through the adjustable middle seat was easy. Little touches, like individual vents and fan controls in the far rear, reminded you of the premium approach of Land Rover in each of its vehicles.

If I consider my car an appliance, then I might turn to Consumer Reports for guidance—but I consider my Land Rover to be a unique class of vehicle with multiple capabilities. When Consumer Reports writes “Most Sports will discover a parking spot at the mall before blazing a trail,” they’re not talking to me, or I’ll bet, you.

It’s a real Land Rover, one I’ll add to my list to Santa Claus.