Last October, I became a verse in the song, “The Day They Drove Old Dixie Down”; another carpetbagger walking off with a slice of Virginia history. “A faux soldier of fortune, a jackal on the track of a lion waiting for it to subdue its prey,” to quote an eminent Southern historian.

This time, my prey would be a storied Virginia artifact, the ’67 109” Station Wagon formerly owned by George William Rickman, Jr., known as “Bill” [see Winter 2019 and Summer/Fall 2019 issues -ed.] Rickman helped create the Rover Owners Association of Richmond and brought his 109” to the “First Annual Virginia Land Rover Caravan,” September 24-26, 1976. The Rover Owners Association would become the Rover Owners of Virginia; the Land Rover Caravan would grow into the Mid-Atlantic Rally.

Bill Rickman purchased the 109” in July 1972, while on vacation in North Carolina. It cost $2,050 at Nowell’s Sports Summit Motors in Wilson. Francis Eubanks Nowell appended a note that the Land Rover “was taken in trade” and was “sold as is — no warranty.” Bill’s trade-in of a 1969 Toyota knocked $1,000 from the purchase price.

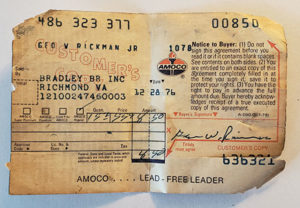

The Rickman family had spent decades with the 109”. Letting go of it took a few months and once again, it was “sold as is — no warranty.” Upon examining the artifacts buried in its nooks and crannies, I discovered that gas at the Bradley Brothers Amoco in Richmond went for 42.5 cents/gallon in 1975, skyrocketing to 55.9 cents by the end of 1976. Another sale slip informed me that Mr. Rickman liked the 96-cent burgers at “Hardees Hamburger.” In the 114-page Series II owner’s manual, 21 pages cover “optional equipment,” from door locks to capstan winches. An assortment of seat cushions, valence panels, station wagon door cards, and exterior mirrors allowed me to speculate Mr. Rickman’s efforts to create comfort during his ownership.

After the purchase, I confronted Ralf Sarek, Sarek Autowerke, Glen Allen, VA, with making it roadworthy — on a tight budget. An old folk song described my finances well; “My name is Morgan, but it ain’t J.P.”

My itinerary posed another headache; I fully intended to drive the 109” from its Richmond-area home 500 miles to its first MAR in decades, and then drive it another 812 miles home to Maine.

Ralf and his team put a gimlet eye to the vehicle and concluded that years of sitting in a field had been unkind to it. Structural components, such as the frame and the bulkhead, suffered from significant corrosion. The motor and its ancillaries look like components that had sat outdoors in the weather; the overall condition led to doubts about the brake, fuel and electrical systems. On the plus side, the interior pieces — seats, door cards, gauges — were all present, dingy and dusty, but relatively intact. Also, the wings, doors and rear tub area had avoided significant damage.

The refurbishment needed a plan to avoid becoming a money pit, one that would focus on the most important elements for safety and reliability, admittedly all relative in a Series Land Rover: frame, bulkhead, brake system, wiring harness, drivetrain, and tires. With every system of a Series Land Rover comes several “while you’re at it” opportunities, and while the 109” was in skilled hands in an experienced shop, I wanted to take full advantage of them.

It is simply not worth spending money on a Series Land Rover with a heavily corroded frame and bulkhead. For strength, Land Rover manufactured the frame from steel plates, and unprotected they can and will rust over time. While a skilled welder can replace many exposed sections on the bottom and sides, top sections are difficult to do effectively without removing the wings and/or rear tub. The bulkhead is welded up from many small sections; these panels must remain dimensionally intact as they determine the attachment points to the frame as well as the doors.

My budget-friendly solution was the availability and purchase of a rolling chassis from a ’76 Series III Station Wagon. It featured a known good engine, suspension and drivetrain. This purchase presented Sarek with the opportunity to lift the body off the Rickman 109” and place it atop the “new” chassis.

Lifting the body exposed the chassis and made some replacement work easier, such as the rear wiring harness and brake lines, which would help keep labor costs in check.

My Series III rolling chassis came without its bulkhead, enabling me to retain a “metal dash.” It certainly needed work and Ralf balanced the cost of the patch panels with the needs of safety, strength and my wallet. Access to the bulkhead made installing a new clutch/brake reservoir and hydraulic lines quicker — also helpful to balancing my budget. Given how long it had sat, I requested a new fuel tank, fuel lines and carburetor. There’s no question but that the small differences between the Series IIA and III made their lives more difficult, and that I could have saved money if a IIA rolling chassis had been available.

Although the motor was a known “good one,” test drives prior to my arrival had left the team surprised at how pokey the 109” drove; it had little power, even with its new Weber carburetor. To my ears, it sounded rough. Removing the distributor cap revealed the central shaft had some wobble, so I ordered a replacement distributor, complete with fresh points, rotor and cap, and new spark plug wires. Installing it the following day, my heart sank when the running condition did not improve with the new ignition setup.

We removed the spark plugs to perform a compression test; the black spark plug tips matched my increasingly black mood. A short while later, the compression and leak down tests confirmed the worst. Two days before our departure to MAR, we confronted the need to remove the head. Once exposed, I had to admit that I’d never seen a head gasket as blown as that one. With little time at the end of a workday, I feared the 109” would not return to MAR 2019.

Then the Sarek team demonstrated why you should partner with a Land Rover specialty shop. Everyone stayed late to remove the head, check it for straightness, clean the block and piston tops while checking each for solidity. When the new gasket arrived the next morning, we installed it, torqued the head bolts in sequence, crossed our fingers and started it up. It hummed like a new motor; I wanted to hug it!

Gene Schubert from Rovers North arrived in Richmond to join me on the 500-mile round trip drive to MAR. Before we left, Gene’s practiced eye determined that the front wheels looked cock-eyed, far out of alignment. Once properly aligned, the Sarek convoy departed with Mitch Medley’s newly refurbished 109” soft top, Jonathan Crain and Ralph Sarek’s modified Range Rover Classics, and me. The landscapes of rural central Virginia were stunning. At one stop in front of a few houses, we attracted an eager crowd of children who had never seen Series Land Rovers before, and their parents, who appreciated our entertainment of their kids.

We arrived at MAR that night and the following morning, I noted that I had a brake system leak. That prompted the purchase of additional brake fluid and a 15-minute conversation with a mechanic who “hadn’t seen one of those in years!”

Rovers North has supported the Rover Owners of Virginia (ROAV) and the Mid-Atlantic Rally (MAR) for decades, in addition to creating and operating an RTV (Road Tax Vehicle) Trials Course at the event. This year, the RTV course benefitted greatly from Gene’s creativity and physical labor. It took us a day and a half to ready it. Gene’s changes leveled the playing field for MAR veterans — adding excitement and the element of surprise to the trials course.

On every trip to Virginia for a Land Rover event, I’ve sought to blend in amongst the hundreds of enthusiasts who inhabit the state. It works, sort of, until I open my mouth. Then my accent identifies me immediately as someone from a Commonwealth other than Virginia. This was driven home when I spoke briefly at last October’s Mid Atlantic Rally. After only a few words, Doug Crowther, Concord, VA, rose to offer “simultaneous translation for Southerners.” Gales of laughter followed, for what I felt was a rather long interval. As a native Californian, Gene speaks in a neutral tone, sans any dialect or inflection that renewed lingering bitterness between the North and the South.

At the end of the MAR I convoyed back to Richmond with Gene and the Sarek team to determine why I had ineffective brakes. We found burst seals in an old wheel cylinder had flooded the new brake shoes. Safety over valor meant replacing the cylinder as well as the shoes and tackling the difficult task of bleeding the 109’s brake system. By then, Sarek was ready to see the taillights of the 109.

I prepared for the drive to Maine. For tools, I bought an electrical repair kit with test light, wire, crimping tool and connectors, a set of SAE ratcheting wrenches, and a screwdriver. I carried extra oil, Girling hydraulic fluid and coolant — oh, and a AAA card, a credit card and some cash. I said my prayers, fired up the 109 and left for home.

A short drive to fill the gas tank revealed that the fuel sensing unit did not report anything to the fuel gauge, and the speedometer would only work for a short while until it broke the new cable. Fifty miles later, I felt the brakes binding and could singe my hands on the front wheel hubs. I released the adjusters on each side and returned to the open road.

My route took me around metro regions like Baltimore, Harrisburg, Newark and New York City, and by doing so, I enjoyed constant reminders of the beauty of our rural settings and small towns. The 109” elected excitement and interest — you would have thought it might have been a Ferrari or Lamborghini for all the stares and conversations.

Cellphone apps made up for the missing information, or so I assumed until I ran out of gas in Port Jervis, NY. I was just working my way through the AAA automated voice system when I heard a lawn motor in the distance. A very generous FedEx delivery worker gave me a ride to fill her gas can, and not long afterward, I returned to the open road. To my delight, the amazement of island neighbors and the relief of Ralf Sarek, that was my only other mechanical issue on the trip.

Puttering along at 55-60 mph made the trip a journey and the experience unforgettable. It even gave me enough time to christen the 109 as “Rickman the Virginian”. I think I’ll change my tune to The Proclaimers’ “King of the Road”.