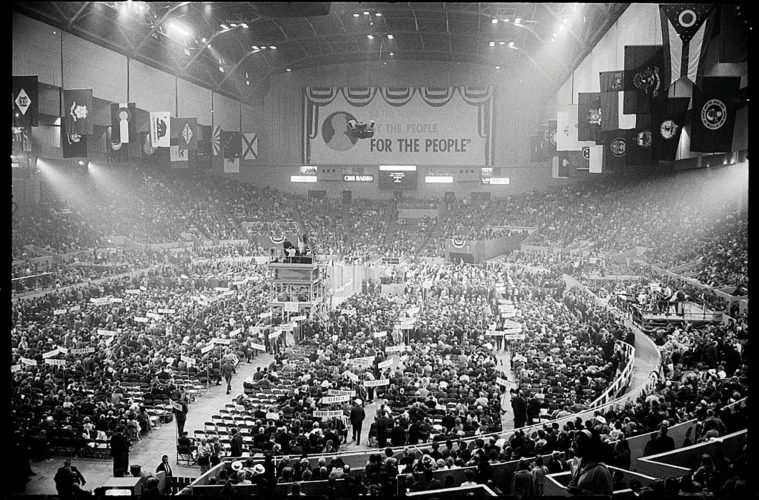

As I write this column, winter has arrived in New England, replete with icy cold temperatures and bracing winds. Over in New Hampshire, February becomes the culmination of the New Hampshire presidential primary. This year, 33 candidates, their handlers, consultants, staff, volunteers, followers and media have trampled through the snow in their quest for victory.

New Hampshire has a history of quixotic presidential campaigns. Back in the 1988 New Hampshire primary, I donned a suit and tie at New Hampshire Public Television and found myself at the network’s studio monitoring the 15 minutes of airtime granted to each candidate. One memorable contender for the Republican nomination announced on the air that he had borrowed his mother’s Cadillac from their home in Buffalo, NY, to campaign in New Hampshire. He proclaimed that ancient Farsi texts, which he could read and translate, linked the survival of whales to current conditions on earth. He closed by stating he needed a place to stay that night, and gave out his mother’s phone number should anyone have an extra room. (Indeed, a young viewer called in to say his folks were out of town and the candidate could crash there.)

What does any of this have to do with Land Rover? Since its return to the US in 1987, the company has — understandably — remained fervently apolitical. However, in this century, it’s hard to hold that stance. A 2005 column in the New York Times contended that data analysis demonstrated, “Land Rovers registered as very Republican vehicles.” A 2012 Forbes commentary using the data analysis asked, “What do Republicans Like?” Cracker Barrel, Outback, Arby’s and Chick-fil-A restaurants, The Office — and Land Rovers (Democrats lean Subaru.)

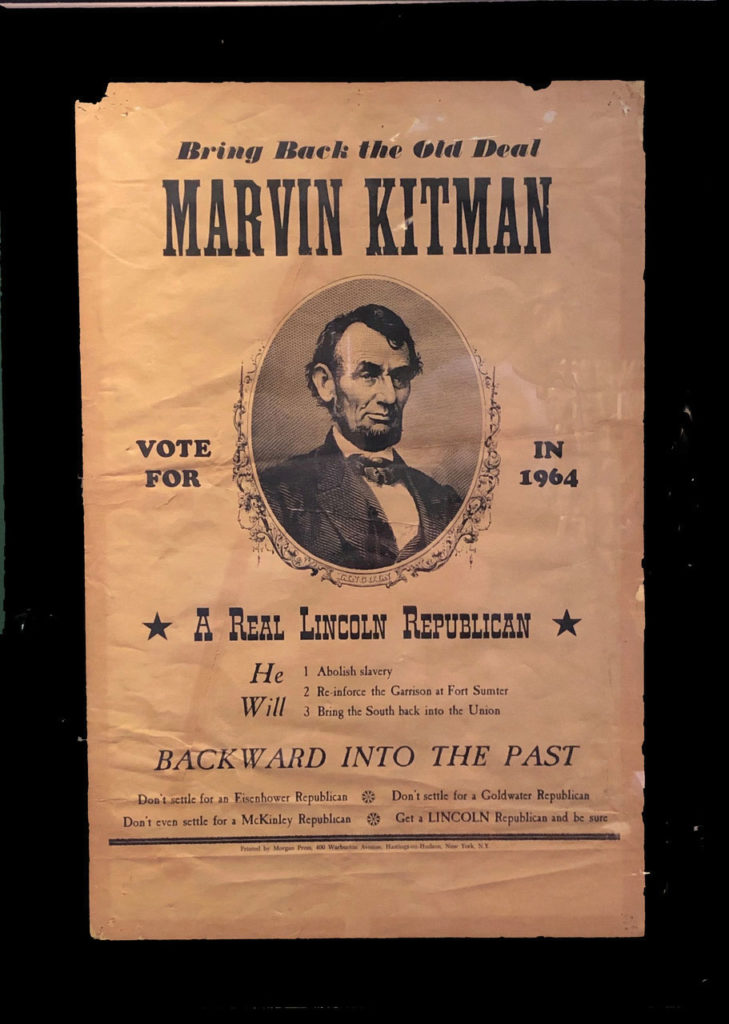

But in 1964 election season, during its previous life in the US, Land Rover lent its good name — and a brand new 109” Station Wagon — to Marvin Kitman, a self-funded candidate. The critic and author recently celebrated his 90th birthday (“Highly overrated”) and consented to an interview to reminisce about his campaign.

A staunch Republican, dismayed by the rifts within his party, Kitman ran as “the only Lincoln Republican. I lost, by the way.” He proclaimed, “the GOP had yet to fulfill the platform promises from 1864,” such as reinforcing the garrison at Fort Sumter, and bringing the South back into the Union. His campaign slogan thus became, “Backward Into the Past.”

How did this satirist secure a Land Rover for his campaign?

First, he had friends in high places, in this case the maverick advertising agency executive, Howard Gossage. His Freeman & Gossage agency in San Francisco had the Rover Car Company account. Saddled with a modest advertising budget, Howard Gossage nevertheless created brilliant ads. In one, he parodied a famous Rolls Royce tagline (“At 60 mph, the loudest noise in the new Rolls Royce comes from the electric clock”), proclaiming that, “At 60 mph, the loudest noise from this new Land Rover comes from the roar of the engine.”

Gossage’s counterpart at the Rover Car Company was Gertrude “Jimmy” McWilliams, whose own desire to attract attention had the company participate in a Gossage-driven “Do You Hate Billboards?” campaign. That effort so enraged California Congressman Bob Wilson that he entered a formal complaint into the July 23, 1963 congressional record. This was not a bashful team.

McWilliams jumped at the chance for the Rover Car Company to support Kitman’s entry into the New Hampshire primary. Since the British call running for office “standing for office,” she arranged for a platform to be attached to the rear of the 109” from which Kitman might, er, stand and deliver stirring speeches.

Land Rover advertisements promoted his candidacy. “We are surely proud of having a Land Rover as the vehicle from which you will stand for office. Land Rovers have been used for various purposes, honorable or otherwise, but never, to our knowledge, has a candidate for office made use of its great go-anywhere features to carry a campaign to the people.”

Kitman would return the favor in a statement that ran in a subsequent advertisement. “In my line of work, the campaign car is key to success. I’m proud to say that Land Rover is my official campaign car. I have made no promises to the Rover Company for the free use of their campaign vehicle. But if my Secretary of Defense wants to use Land Rovers instead of Jeeps, I will not stand in the way. They’re already used in 26 armies and 37 police departments the world over.”

“The Land Rover’s easy attachments make campaigning so easy. My model has a platform on which I can stand squarely at all times (except when driving.)”

“What I like about the Land Rover is that it goes anywhere. In New Hampshire, it took me right up the ski slopes, solving one of my most vexing problems as a politician. I don’t like to shake hands. My Land Rover made it possible for me to park next to the ski slopes and personally wave to 3,000 votes as they went by — none the wiser.”

“Because the Land Rover is imported from England, I can technically say that I am the only candidate in the Republican presidential primaries who is ‘standing,’ rather than ‘running’ for office.”

“If you, too, are planning to run for President, or even Prime Minister, I would like to call your attention to the virtues of the Land Rover as the perfect campaign car.”

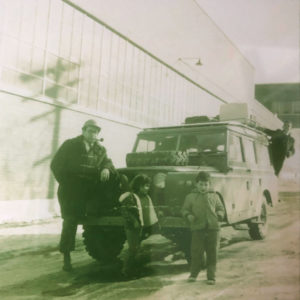

With funds limited, the Kitman campaign determined that they could afford only a weekend visit to the Granite State. The idea was to stop in as many towns and cities as possible, suggesting that, “It would be good for their economy. As a ‘man of the people,’ I did my own driving.” The 109’s passenger manifest included: Victor Navasky, his campaign manager, Richard Lingman, his speechwriter (both fellow conspirators from Monocle, their satirical quarterly), his wife, Carol, baby-sitter, Johnny Peck, and the Kitman progeny, Jamie (age 7) and Suzy (4).

For Jamie Kitman, now a well-known automotive journalist, the trip enabled him to skip school and take a road trip. He remembered, “None of it made any sense to me at the time, but today, examining the vast historical record (which consists of some newspaper clippings, a couple issues of Monocle, and a 45 rpm pressing of the peppy campaign number, ‘Sing a Song of Marvin Kitman’), I gather that 725 of New Hampshire’s concerned Republicans cast their lot with my father, which is more than I would have guessed.”

Jamie has called his adventure in the back of the 109, “Cold, despite the Kodiak heater, but deeply, undeniably, cool. That’s why I spent the next 30 years pestering my old man to buy one. Such are the seeds of madness.”

Despite his loss in the New Hampshire campaign, Land Rover continued to support Kitman in his political endeavors. One issue during the ’70s involved steel companies seeking to raise prices against the wishes of the federal government. Although a relatively small firm, Wheeling Steel found itself in the middle of the political and economic debate. Kitman, a child of the Pittsburgh region and a staunch supporter of free enterprise, wrote to the president of the beleaguered company with an offer to buy one ton of steel for $137. To his shock, Wheeling’s CEO accepted and staged a big ceremony, and once again, Land Rover made a 109” available to him.

Kitman remembered, “There was quite a storm that day during the drive. I got there and Wheeling Steel had put on a major presentation. They had created a slab engraved with my name, like a plaque. The workers embedded a big hook on the slab to hang it on your wall. It was loaded into the back and I’m proud to say the Land Rover could handle it.” The question then became what to do with the giant plaque once he got it home. “The whole staff of Monocle carried it out onto my lawn as a shrine to free enterprise — and it’s still there.”

Kitman continues to write — his latest book is Gullibles Travels — and publish sharp satire, sharing his caustic yet entertaining observations at www.MarvinKitman.com. He missed the deadline to get his name on this year’s New Hampshire presidential primary ballot, but with Land Rover lengthening the wheelbase on the new Defender 110, he could campaign in greater comfort during the 2024 election.

Should he decide to run on a more historic platform, one that would permit him to relive the cold and discomfort of his 1964 campaign, I would certainly loan him my 109”. By 2024, I should have completed the installation of a new door and scuttle vent seals, perhaps even upgrading the “fug stirrer” heater to the Rovers North Mt. Mansfield Heater.