The Powerball payout during the week of September 9 totaled $75 million. Given what happened that week, I should’ve bought a ticket. I would have won.

I’d received an email from Allan and Sally Seymour, Land Rover North America’s long-time photographers and videographers [see Summer-Fall 2020 issue]. They would be sailing along the north shore of Vinalhaven island and asked if I could meet up with them the following morning. On the appointed day I jumped into “Rickman,” my ’67 109” SW, and drove to the public landing to meet them for our “meet-cute.”

When I pulled into the tiny parking lot, I saw a large power boat tied off at the dock. Six people were loading expensive-looking video gear, lights and drones onto the deck. A young man ran up to me, saying ”Wow! You have an old Defender. Look at the one on the barge in the channel!” He pointed to a freight ferry steaming toward shore. Sure enough, on an open deck, there sat a new, Tasman Blue Defender. “We just finished filming over there [the adjacent island of North Haven] and we’re bringing it here to continue filming.”

I was about to argue the point of whether a Series IIA should be called a “Defender” when I saw a skiff coming across the channel with the Seymours aboard. “See the skiff out there?” I asked the crew member; “Decades ago, that couple did all the location video and photography work for the NAS Defender, the same work you’re doing now for the new one!” While the Seymours met the Outside TV crew, I tied off their skiff to join in the greetings.

We stood there, stunned at the coincidence. “What are the chances?”we wondered. It felt like a moment from Black Mirror or The Twilight Zone.

Chris Crowley, the Executive Producer of Outside TV, introduced himself as a NAS Defender 90 owner and a reader of Rovers Magazine. A multi-media corporation, Outside has partnered with Land Rover often and has use of a 2020 Defender 110 for their productions. The crew would now head out to an old farmhouse location at the mouth of a nearby cove. Once Chris said who owned the property, I knew its location; over the years, my Land Rovers have hauled a lot of equipment and crew members to work on their grounds.

I drove to the filming location in time for the end of their lunch and the start of the afternoon shoot. Not only would the Defender stand in as the video star, but Outside had brought mountaineers Emily Harrington , Adrian Ballinger, Noah Kleiner and Mark Synnott as part of their program. Emily Harrington, Squaw Valley, CA, has won the US Sport Climbing Championship, has summited Mt. Everest and more recently, became the first female to free-climb the 3,000 ft. Golden Gate cliff face of El Capitan in Yosemite National Park. British-born Adrian Ballinger, now in Olympic Valley, CA, leads expeditions up the world’s most challenging peaks, including multiple groups to the summit of Mt. Everest, and as a professional athlete, holds world records for skiing down multiple 8,000 meter-tall mountains. Noah Kleiner, Equinox Guiding Service, leads rock and ice climbing adventures along the coast of Maine. Mark Synnott, Jackson, NH, holds an impressive number of record climbs and mountain ascents, has published two best-selling books and appears in National Geographic and on NBC. He has also served as climbing guide to the cliffside faces, accessible only from the water, that would become the theme of this episode.

What brought these famous climbers to Vinalhaven? I learned that Outside TV had reached out to Noah Kleiner for recommendations along the coast, and Noah had connected with his film production friend (and seasonal island resident), Tyler Dunham, of MakeWild to find the best island location. (The fact that I stumbled onto this event on the day of the Seymour’s visit still boggles my mind.)

At the waterfront site, I stood, green with envy, listening to the famous mountaineers extolling their time in the new Defender. (I also met their dog, ironically named, “Cat.”) I suggested that they might want a ride in my blue ’67 109” and that I’d suffer with the new Defender; Emily and Adrian declined pleasantly. I stewed over the fact that Land Rover had not delivered a new Defender on a barge to me. Also, Outside TV had ignored my successful summiting of this island’s 118-ft-high Big Tip Toe Mountain, an achievement that admittedly most of this island’s schoolchildren accomplish each year.

No one filmed my previous ascents of Big Tip Toe Mountain, but you can watch Emily, Adrian and Mark climb cliffs on this island on the Outsideonline.com website.

On occasion, my Series Land Rovers will choose to embarrass me with an inconvenient breakdown. The latest was the QE I, back in November. I had just driven out of my yard and diagonally across my narrow street when the IIA stalled. Naturally, that’s when my next-door neighbor, heading to work as a fuel oil delivery man, drove his truck onto the street. I waved an apology and pushed the starter button – all I could hear was a grinding noise. The starter did not turn the flywheel, which meant that the QE I would not budge. It took two of us to push the QE I backward and downhill into the yard.

Thinking that the starter’s mounting bolts might be loose, I crawled underneath to wiggle it. With very little movement present, I assumed that the high-torque starter, installed over a decade ago, had failed. I had two options on hand: a rebuilt Lucas starter, which weighs 25 pounds, or a Proline High Torque starter, half the weight and 3 inches shorter in length. When you’re lying on your back and lifting the starter over your head – backwards – underneath a Land Rover, trying to start a bolt blindly with your other hand, size does matter.

I disconnected the battery and unbolted the cable from the starter button. Using a socket and extension I removed the top bolt, which is always hidden from view, and with one hand securing the starter, removed the bottom bolt, wiggled the starter gear out from the flywheel ring, and extracted it from around the exhaust header pipe. Not until I crawled out from underneath did I see the near- disintegration of a starter to solenoid wire; not until I removed the starter did I see the broken bolt that had loosened the starter body from its innards. No wonder it just didn’t engage. I slid the new Proline starter into place, bolted it up, connected the battery cables, and the QE I fired right up. And, if I need additional weight training, there’s a 25 lbs Lucas starter ready for my pandemic regimen.

The United States owes a lot to Canada; not least is their ability to satirize us. The list of “I didn’t realize they were Canadians” ranges from SNL’s Lorne Michaels to Samantha Bee, to Ivan Reitman of “Animal House” and “Ghostbusters,” Mike Myers of “Wayne’s World,” Jim Carrey, Ryan Reynolds, Seth Rogen, Dan Aykroyd and Catherine O’Hara, among many others.

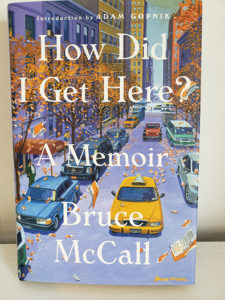

If you’re an auto buff, you really must thank Canada for Bruce McCall. His satires employ language and art from his life in advertising, automotive journalism, magazines such as The National Lampoon and The New Yorker and television programs like Saturday Night Live. An earlier book, The Last Dream-O-Rama: The Cars Detroit Forgot to Build, and his recent memoir, How Did I Get Here? (Blue Rider Press, New York), explore his inherent affection for the automobile and make him a delightful read.

McCall wrote advertising for Ford and General Motors, which led him to create brilliantly satirical American cars such as the Bulgemobile Blastfire, the Ticonderoga Custom El Mocambo station wagon, the Glamoramic Polo Lounger Funtop, the Atomikar and the Bongo Beatnick Ferlinghetti Turbo-Hipster.

As a British car guy he took pride in his time with his Ford Anglia, Morgan Plus 4, and Triumph TR-3; those experiences led him to create mock test drives of the Denbeigh Super-Chauvinist Mark VII Saloon, “the performance of which was not torrid but beautifully matched to the brakes, which fade as one.”

He poked fun at the language of owner’s manuals: “Attempting to drive your car with a pedestrian underneath can cause uneven tire wear, front-end misalignment, binding of the steering gear, and damage to the catalytic converter in your exhaust system, creating an environmental threat that may increase the danger of global warning.”

Most importantly, McCall rues the changes in the automotive experience. “Since my time working on car ads, automobiles have morphed into emotionally neutered large appliances, competing more on entertainment than performance, dulling risk with technological interventions that replace the need for judgment. This is good for safety and inarguably progressive – but it’s heading into a tomorrow where we’ll all be guests in our automated, self-driving blobs. Driving under the proper conditions – the right kind of car… responsive to the slightest touch – made driving a sport and a pleasure, with a frisson of underlying danger to penalize a lack of skill. I look back and see that I had lucked into the romance of driving at its fervent peak.”

I know that my Series IIAs and Discovery I will always remind me that I’m not in an appliance, but in a vehicle, for which I’m responsible as a driver. Otherwise I might as well own one of McCall’s mythical cars such as the Quickfire 5000 Jackpot or Nixoneer Squelchchroramic.