Nearly fifty years ago, as a student at Exeter Academy in New Hampshire, I heard a presentation by Rodney Marriott, an English teacher, about a nearly year-long expedition in which he took students from Exeter and Dartmouth College through several African nations. He wanted to recruit a new group for another expedition. As a teenager, it seemed like a fun way to get away from my family (the feeling might have been mutual).

Two years later, at age 17, I joined 20 friends in driving four Series IIIs from England through France and Spain, across the Sahara Desert, through West Africa to Cameroon. We were an informal group, with ages ranging from 15 to 65, linked by our common desire to experience different cultures. It took a year of planning and provisioning, which for me, included my first-ever, late-night trip to L. L. Bean. $2,000 later, I had the clothing and supplies I thought I needed for the 7-month trip.

Upon our arrival in London, we traveled straight to the Land Rover factory at Solihull and picked up four, brand-new Rovers with consecutive serial numbers. Three had two bench seats, with seating for six each; one Land Rover, named the “Cook Rover,” carried only three people and had extra storage for food and supplies. We spent a couple weeks at a camp site in Stratford-upon-Avon kitting out the Land Rovers (and going to the Royal Shakespeare Theater). We bolted on iron roof-racks with home-made plywood boxes covering almost the whole length of the roof of each vehicle. Once in Africa, we would discover that the roof boxes also shaded the interior, making it a tad more comfortable in the insane heat we experienced later in our travels. It takes a lot of equipment and provisions for 21 people to camp out for an extended period in sometimes very remote regions, but we managed to fit it all in – and onto – the heavily laden Land Rovers.

France and Spain went by pretty fast and served as a shake-down cruise, but we were eager to arrive in Africa. Once we arrived by ferry in Morocco, it felt like we had entered a different world: the periodic calls to prayer emanating from loudspeakers, the narrow streets winding through high sandstone walls with thick wooden doors in them, the little shops tucked away out of sight with salesmen who wanted to sit you down and serve you tea as well as sell you something. We spent a week there preparing to cross the Sahara.

For us, the Sahara did not include the miles of drifting sand dunes we’d imagined. Much of it was an almost featureless flat gravel expanse for miles and miles. It was also hot that July – the temperature routinely rose to over 110 degrees every day, and over 115 on some days. Of course, we had no air conditioners and discovered that driving in temperatures that hot is more comfortable with the windows closed; you don’t want such hot air blowing on you. Our routine was to stop and lay sweating in any shade we could create from about 1–4pm, then continue driving till sunset.

The longest distance between fuel for us was 500 miles. We had multiple jerry cans of extra fuel and jugs of water on the roof racks. About halfway across that 500 miles was a small village outpost of mud huts with not an ounce of vegetation anywhere in sight. They sold us some water from their well. We never drank that water because it looked and smelled so bad, but, like taking a sailboat across an ocean, when crossing the Sahara you want to stock up for any possible emergencies. That village had a bunch of children in it who came out to ogle us; I tried to imagine growing up never having seen a tree – or hardly anything growing out of the ground.

I hadn’t even had a driver’s license for long when I started this trip. Before it was over, I’d spent more life-miles driving on rough dirt roads than on pavement, and some were very rough. Even in the Sahara where we could sometimes see the next five miles of flat gravel ahead, we couldn’t go too fast because a hidden rocky ditch or outcropping would suddenly appear. It was safer to go slower; breaking down in the middle of the Sahara with that extreme heat becomes a life-threatening emergency faster than you’d think.

Navigating in the Sahara mostly meant following other vehicle tracks, though occasionally there would be a 55-gallon drum we might spy on the horizon denoting the route. Sometimes the tracks we were following would go off in several different directions and we would have to pick one. Sometimes the one we picked was wrong, and it would take the lead vehicle into a sand pit. We had some metal sand tracks and the Cook Rover had a winch, so we always got unstuck relatively quickly, but sometimes we’d have to peck around to find the drivable route through the sand.

When we finally got to Nouakchott, Mauritania, not only were we able to bathe for the first time in several gritty, sandy, sweaty weeks, we camped for a couple days at a place with a swimming pool. The relative luxury of that pool might be the greatest sybaritic pleasure I’ve experienced in my entire life.

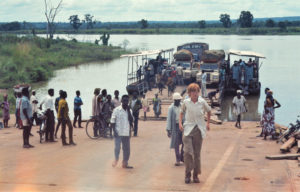

The Sahara landscape ends and a tropical jungle emerges surprisingly fast along the coast in Senegal and Gambia, and the next 3,000 miles of our trip – except for a part in northern Nigeria – was mostly jungle driving. A lot of West Africa is connected by dirt roads that become muddy, slippery and rutted out in tropical rain. There were a few full days of driving where we ended up only 75 or 100 miles from where we started and were glad to have the winch.

We all became fairly expert off-road Land Rover drivers no matter what the roads threw at us. We had radios in each car to communicate while driving, but once, they failed us. Due to the red tropical dust that billowed up behind each Land Rover, sometimes we would travel out of sight of the other cars. One day, the Land Rover taking up the rear had a total electrical break-down and stopped dead in the road, thus having no power for its radio and no way of telling the rest of us of the breakdown. It was quite a shock to eventually discover we’d lost a Rover with six people in it! After 10 or 15 miles of worried back-tracking, we found them just before they finished repairing the broken wire and were ready to go.

We only had one vehicle accident, one for which we should have experienced a premonition. As part of our cultural exchange, we took part in a “medicine man” ceremony in a remote village. Sitting in a circle in a dirt-floored hut, we watched chanting and dancing. Suddenly, the shaman turned to the oldest member of our group and directed stern words to him. We had a translator who explained, “The priest says you have angered the iron gods and must make an offering to them or else something very bad will happen.” We made the suggested offering, which seemed to satisfy our hosts (and hopefully the iron gods).

Two days later, on a paved road in a torrential downpour, one of the Land Rovers – which happened to have the same oldest member of our group in it – lost traction, spun and flipped over 360 degrees. It landed on its feet with no injuries and no harm except a minor crunch of one corner of the roof rack. They drove away as if nothing had happened. The iron gods went easy on us!

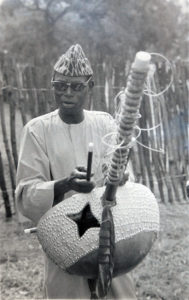

Some members of our group had planned to leave after three months; I left after seven months, but a contingent continued their travels as far as Kenya. For me, my seven months of travel by Land Rover led to a thousand adventures, big and small. Suffice it to say that, in 1973, West Africa was a wonderful place to explore. The region exuded an exciting, post-colonial joy and innocence. Everywhere this 17-year-old boy went, he was greeted with pleasure, invited into conversation and even invited home to meet the family. As a more or less typical American teenager, I was mystified how the Africans I met who often owned little more than the clothes on their backs were so happy and joyful. Singing and laughter and dancing (and drumming!) were as common an activity as television in the States.

Several Africans I met told me of the saying that once you visit West Africa you will always return. As it happened, I did so in 1986, this time by tugboat to the Ivory Coast and Nigeria – but that’s a different story.