Jim Koenigsaeker, Sacramento, CA, grew up on a farm in Muscatine, IA. “We had a little green International Scout pick up on our farm,” he recalled in a phone interview. “My one channel on TV carried the Wild Kingdom, so I came to like Land Rovers.”

He calls his ’65 Series IIA a “Frankentruck,” and has owned “parts of it” for 25 years or more. “I bought the ‘barn find’ RHD pickup about 6 years ago and swapped out a bunch of parts, including the motor, drivetrain, and top. The Rover was a faculty vehicle shipped to the US for emissions testing, hence its ‘X’ plate. Another reason I like this Land Rover is that the factory had obviously built it from parts it had lying around, including an SWB Australian military chassis.”

Mark Twain once worked for the local newspaper in Muscatine, and Jim began in Twain’s footsteps as a newspaper delivery carrier on a morning and evening route. The newspaper was part of the Scripps Howard group, so it’s no surprise that Jim moved on from a paper route to the Scripps School of Journalism at Ohio University. His career path took him to Washington, DC, where he covered the Clinton administration. “At the time, Scripps Howard was the second-largest newspaper chain in the county,” Jim recalled, “so our seat in the White House Press Room was right next to the famous Helen Thomas.”

Twenty years ago, Jim said, “through serendipity and good luck, I fell in love again with Africa when I was invited by a friend to go to East Africa. I felt like I was in a Hemingway novel. Every generation has bemoaned how Africa has been ruined, but it’s still wonderful.” When he’s not there, his RHD Series IIA reminds him of his beloved East Africa, where RHD Land Rovers are commonplace.

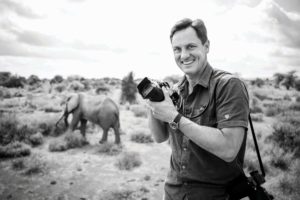

Jim told remarkable stories of his service work through photography; my envy level went through the roof.

“I wanted to help keep [Africa’s] past intact, so I help with little philanthropic projects. Some DC friends have helped, as well as a motley crew of friends in Kenya. I stay on the grounds of the Karen Blixen Museum [See “Out of Africa” -ed.] – she grew up on the ranch with wildlife, but it’s now surrounded by the ever-expanding Nairobi. I actually thought of moving there, but family reasons have kept us in California.”

“I got really involved in wildlife technology, a sort of Fitbit for a lion or leopard. We place a collar on a matriarch and that feeds data for her location. If she and her pride intrude onto farmland, we can deploy teams of rangers to track the apex predators and try to mitigate conflict with farmers. The collars are maybe $500 and a cheap cell phone will receive the data. Now you don’t need aircraft or a large infrastructure to track them. I serve with Masai friends, and Skype and cellular technology have worked quite well. Small-scale solar power has also helped with our work, as well as for life in general. Mobile banking has been a facet of African life for a long time.”

“The rapid response team of rangers are in Series Land Rovers and early 90s/110s – the Land Rovers just keep going. Every time I’m there, I’m always in a Land Rover; it’s my sidekick. Before the pandemic restrictions, my last trip was to Lake Turkana, a World Heritage site. I’m trying to document these world sites, as they’re threatened by the Nile River dam in Ethiopia and its potential oil deposits. The Turkana people who populate the region live nomadically as they’ve done for centuries.”

“This past summer, I returned to Kenya and worked with the Kenya Wildlife Service, the Mara Elephant Project, the El Karama Conservancy, and Safari Doctors. I always stay in El Karama when I’m in East Africa. I have been friends with the family that started that conservancy for almost 20 years. Bella’s parents founded El Karama and she is married to Michael Nicholson, the head of Kenya Wildlife Service Airwing.”

The trip involved an epic, 15-hour, mostly off-road drive over the Aberdare mountain range. “I did not see another vehicle from El Karama to Naivasha or from Narok to Marc’s camp on the Masai Mara,” Jim recalled. “The trickiest bits were getting to and from the remote camps in the bush in the darkness before and after long days of driving..”

“The highlight of the trip for me was photographing one of the last of the “Big Tusker” elephants, known as Craig, in the Amboseli National Park. Amboseli is a United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization, Biosphere Reserve. The Big Tuskers are elusive and rarely seen by tourists. And the rangers keep their locations secret to protect them from poachers. I spent two, very long, dusty, bumpy days in the bush looking for Craig.”

“Then, as the sun was setting on the second day, the clouds broke, giving me my first view of Mt. Kilimanjaro on this trip, and Craig walked out of a thicket. Usually, wildlife is photographed from a distance with a telephoto lens because it is difficult to get close. But I wanted to photograph Craig at very close range with a wide-angle lens to try and capture the feeling of awe you get when you are close to these magnificent creatures in the bush.”

“I have been fortunate enough to spend a fair amount of time with elephants in the bush over the years and know that they are incredibly intelligent and keen judges of character. They also make it very clear when they do not like something by rearing up and spreading out their ears as a warning. So I very slowly crept up to a few feet from Craig as he calmly continued walking along and eating. He seemed to be at peace, not upset with me at all. Needless to say, I stood in awe of this experience.”

I connected with Jim through his friend, Mike Blanchard, the Editor of Rust. Mike wrote that “Africa is his thing. I’m sure he will keep going back as long as he can. It’s a cliché, but Africa, especially East Africa, seems to get its hooks in people and keep pulling them back.”

My envy level has not dropped one bit.