This year marks the Silver Jubilee of my relationship with my 50-year-old Series II-A. I bought it in 1991, the same year I decided to go freelance. My other car at the time, a 13-year-old Triumph Spitfire, had demonstrated some fragility in daily use. Since I had previously owned soft top Jeep CJ’s, water leaks, drafty doors and overall discomfort seemed normal to me, and previous British sports cars had familiarized me with dodgy electrics and pitted points. However, my knowledge of Land Rovers matched that of a seedling flung into unfamiliar terrain. Oil bath air filters? Swivel balls? Floating axles?

At 111,000 miles, the QE I had led an interesting life under the ownership of an off-road enthusiast known as “The Terminator.” My grueling road test consisted of puttering around farm fields at 15 mph on a warm, sunny day. Blissfully ignorant, I pronounced it fit and bought it. When I finally screwed on license plates and drove it on the road, I discovered that the four mismatched retreads made for interesting handling and that hitting a bump would dislodge the fuse that controlled the wipers and gauges. By 165,000 miles, the engine averaged 80 miles per quart of oil, and a rebuilt engine from Rovers North found its way into the II-A. While it survived a collision with a horse, a 2003 incident with a deer exposed significant frame and bulkhead rot. Rebuilt by East Coast Rover with Rovers North parts, it now has accumulated over 520,000 miles.

Life with my Land Rover has necessitated a mechanical learning curve on my part, much to the amusement of the Rovers North technical staff. Most recently a slow loss of brake fluid and diminished braking action forced me to look underneath, where I discovered a rear wheel brake cylinder leak. I ordered the cylinder, new shoes and a spring set from Rovers North. Removing the wheel and drum uncovered quite a layer of La Brea tar pits ooze on the shoes and a broken top brake spring. Even after 25 years I still get confused over the placement of the top spring, but a quick check of the tech tips on the Rovers North website straightened me out—for now.

Series Land Rovers and Defenders were simple but never crude, well-engineered but designed for maintenance in far-flung places, like an island off the coast of Maine. Given my mechanical limitations, I’m confident I’ll keep the techs at Rovers North laughing for another 25 years.

A 1969 Land Rover advertisement insisted, “A Land Rover is not just a rough, tough, go-anywhere vehicle for terrifying trips in jungles and deserts. A Land Rover seats you in soft-cushioned comfort. It’s a smooth cruiser on motorways.” But a 1973 Motor road test asked, “Nobody in their right mind would now buy a Land Rover for ordinary road transport (would they?), for its performance is low and its comfort minimal.” I had a chance to test out these contending viewpoints on a 700-mile round trip last December.

With a fresh set of BF Goodrich All-Terrain M+S’s, tire noise would be high; combine that with the usual gear whine, road vibration, engine roar and wind noise, and the decibel level inside would rise to a cacophony. The QE I did not disappoint me. It sounded like I sat inside a trash can while someone pounded on the outside with a hammer. Adorned with a Christmas wreath on the grill, it offered passers-by a friendly yet distinctive look. Since it cruised at about 60-65 mph, I saw many, many passers-by from the far right lane on the interstates.

Over the four-state drive, one Discovery owner waved, while the LR4 and Range Rover owners ignored me through their tinted windows. The guy in the Audi convertible made certain I saw his thumbs up, as did the driver in the Ford pickup who also honked his horn to make certain that I saw his approval signal. At the Hampton, NH toll-booth, the attendant complimented me on “the wreath on your Jeep.” Traffic was too busy to argue the point with her. At a rest area on I-95, a traveler waited to question me about the Land Rover and engage me in conversation about it. Entering the Maine Turnpike, that toll-taker correctly identified it as a Land Rover and took its photo before accepting my toll.

I sat upright in the non-adjustable seats, just like my mother used to nag me to do, and made a few stops necessitated by the limited range of the 12-gallon tank. The Rovers North Mt. Mansfield heater kept me so warm that I had to slide open the window on occasion to keep the cabin comfortable. The Land Rover delighted drivers on the highways as well as my hosts in Connecticut; it even made a cameo appearance in their family Christmas card. It also put a smile on my face.

With much gnashing of teeth and rending of cloth, Land Rover enthusiasts mourned the end of Defender production. Land Rover has promised that the iconic engineering, capabilities and styling of the Defender will be retained, but with significant updating of features and likely a more aerodynamic, less striking silhouette. We North American enthusiasts must remember that our last formal importa- tion of Defenders took place 18 years ago—on a vehicle whose man- ufacture harkened back to 1948. Market expectations have shifted since then.

With much gnashing of teeth and rending of cloth, Land Rover enthusiasts mourned the end of Defender production. Land Rover has promised that the iconic engineering, capabilities and styling of the Defender will be retained, but with significant updating of features and likely a more aerodynamic, less striking silhouette. We North American enthusiasts must remember that our last formal importa- tion of Defenders took place 18 years ago—on a vehicle whose man- ufacture harkened back to 1948. Market expectations have shifted since then.

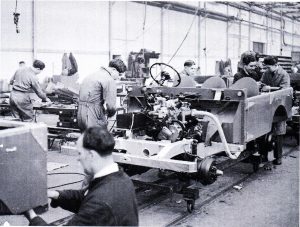

In post WWII England, labor came cheap so vehicles requiring a lot of hand assembly made sense. Those of you who have refurbished or restored your Land Rovers know of the time required to get the job done right. Contemporary Defenders just wind up being expensive to produce—and admit it, we’re less tolerant as consumers of air and water leaks from ill-fitting panels.

Last winter I decided to delay a necessary repair of my Series II- A’s safari top and run a canvas top all winter. Untying the rear window to open the tailgate every time I needed to access the rear proved a pain in the severe winter of 2014-15. So this winter, I determined the make the necessary window track repairs on the safari top and save the canvas top for next summer. After all, I had bought the mouse fur window track kit two years ago, and the entire job is much easier when you can turn the top upside down, too. A buddy helped me carry the top from its storage spot to my front lawn for

the repairs.

To remove the sliding windows, you need to drill out the rivets holding a stainless steel strip in place. Once accomplished, the windows slid out of the tracks. That exposed a line of tiny, flathead screws that held the tracks in place. Amazingly, none required drilling and all could be unscrewed by hand. The kit from Rovers North included new screws along with the nicely lined tracks. I started with the top and bottom tracks, drilling new holes for the screws, and then fitted one vertical side before reinserting the windows. It took a while on that pleasant afternoon to figure it all out, but it certainly tightened up the top.

Now, on an assembly line, all this would have gone faster, but this experience gave me an insight into the labor costs required to produce a contemporary Defender. I’m thrilled to discover that I can do the job myself—but then, I don’t have to pay myself. Land Rover faces an onerous challenge in replacing the Defender with a vehicle built to contemporary market expectations, at a reasonable cost. Let’s hope that the new manufacturing techniques will still make it possible for enthusiasts to maintain their Land Rovers themselves.

Story and photos by Jeffrey Aronson, Mark Letorney