The needs of the world after WWII, when the Wilks brothers and their team created the first Land Rover, helped shape the engineering and design of the “world’s most versatile vehicle.” Great Britain required mechanization of agriculture, construction vehicles, and people carriers—all in one. Before WWII, the Rover Car Company [Land Rover’s parent corporation] didn’t even have an export department. After WWII, Britain’s economic devastation would demand that firms “export or die.” The Commonwealth colonies would become independent nations, but would still have friendly trade arrangements; still, you would need to create a vehicle for all driving conditions that could be field repaired. The niche Land Rover entered might be relatively small, but it extended across 160 markets worldwide and they would absorb every Land Rover the Solihull plant could produce in any year.

Land Rover manufactured its first Range Rover in 1970, a time when Great Britain itself had only created its new “motorway” network. The US interstate system, envisioned in 1957, was still in its in- fancy with thousands of miles yet to be carved out of the countryside or through America’s cities. The newly emergent nations of Asia and Africa would increase the demand for vehicles of all types dramatically. One demographic trend trumped all the political and social issues of the post-WWII world—increasing urbanization. Mega cities were hardly new, but now they grew dramatically in scale and num- ber, regardless of continent. Increasing percentages of every nation’s population will live, work and drive in urban settings—and that change certainly affects automotive manufacturers.

You need only look at a most recent Range Rover Evoque advertisement in a Spanish-language airline magazine. The ad copy read, “The new Range Rover Evoque perfectly evokes the city.” There’s no question, but all the newest Land Rover models have off-road capability built in—underneath the matched grain wood burls and

the leather stitching sits all the engineering and components required for off-road driving. But really, do you want your dog to put its dirty paws on the wood fold down tables? Should you be scraping the mud off your Wellies on the superb carpeting? Shouldn’t you turn off the premium sound system and divert your gaze from the center dash screen displaying your email and pay attention to the off-road marshal spotting you up the trail?

When you meet Land Rover UK engineering and management executives, you can tell that their hearts are in the right place. Yes, Land Rover models are technically “versatile.” Yes, Land Rover must operate in the 21st century, not the mid-20th century. What’s needed is an enduring commitment to create and manufacture a Defender whose engineering and design enables those leading or involved in rural experiences to live it “above and beyond.”

Winter weather in New England brings on a more reflective mood and the opportunity to catch up on reading. Three books on adventures in Land Rovers allowed me to live vicariously through the lives of British, Brazilian and South African travelers.

In the last issue I had the honor of interviewing Martin Hugh-Jones and Mike Andrews, two of the three original adventurers of the “Cambridge Trans American Expedition,” as well as their Alaskan compatriots who accompanied them on the final 500 miles of their long-delayed journey. Mike and Ben Macworth-Praed chronicled the 1960 travels in, A Year With Three Summers. Ted Peterson, who recognized the provenance of the Series II, loaned me his copy of the book. It’s quite a read on many levels, as a cultural history, a reminder of the “road” conditions in rural reaches of Latin America 60 years ago, and of the wonder of discovery through travel. Imagine four men and their non-digital, non-synthetic camping, camera and scientific gear, stuffed into a 109”.

The book couldn’t possibly cover all 43,000 miles worth of experiences, sounds and emotions. Indeed once they hike through the Darien peninsula of Panama, the book picks up the pace and captures their urgency at reaching their Arctic Circle destination in time. In the end, weather, finances and inner exhaustion took their toll and by Fairbanks, they’ve sold the Land Rover for $1,800 and headed back to England.

During their travels they made contact with British citizens and ex-pats throughout the Americas, but they also brought their academic disciplines and professional interests to bear on the indigenous people they met. Many times their bemusement at their circumstances had me laughing out loud.

One revelation arose when the group understood themselves to be “overlanders” rather than visitors, travelers, workers or tourists. They met other overlanders in Land Rovers, rather ordinary vehicles and even a Scottish bicyclist. To overlanders, national borders mean more than just another stamp on a passport; they represent a change in culture, language and landscape. The opportunities for change jump out in front of you. Overlanders don’t just see the world, they experience it.

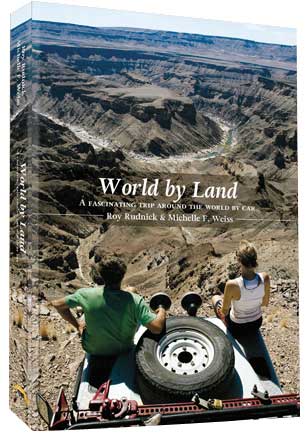

Those chances jump out of the photos and text of Roy Rudnick and Michelle Weiss’ World By Land. This young Brazilian couple left a challenging yet comfortable job and a university education behind to explore their larger world. I met them at the 2015 Overland EXPO last May and received a guided tour of their living quarters. Today’s overlanders are more multilingual than in the past and through digital technology, far more able to anticipate bureaucratic or transportation issues. Yet, their sense of wonder over the foods, sounds, smells, landscapes and people they experienced leaps out of their book. Their enthusiasm for the world made possible by their Defender scrolled its way through every word [see Summer 2015 issue —ed.]

Those chances jump out of the photos and text of Roy Rudnick and Michelle Weiss’ World By Land. This young Brazilian couple left a challenging yet comfortable job and a university education behind to explore their larger world. I met them at the 2015 Overland EXPO last May and received a guided tour of their living quarters. Today’s overlanders are more multilingual than in the past and through digital technology, far more able to anticipate bureaucratic or transportation issues. Yet, their sense of wonder over the foods, sounds, smells, landscapes and people they experienced leaps out of their book. Their enthusiasm for the world made possible by their Defender scrolled its way through every word [see Summer 2015 issue —ed.]

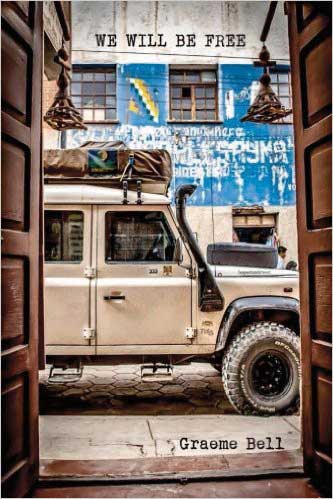

While Roy and Michelle left comfortable lives and supportive families behind, Graeme and Luisa Bell from South Africa grew up in harsher personal and political circumstances. In his book, We Will Be Free, Graeme recounts the broken family and spurious dreams that were made right by the triumvirate of his marriage to Luisa, the birth of his children, Keelan and Jessica, and their Land Rovers. A much loved Series III and an early Range Rover Classic were simply too small for overlanding with a family of four, but an ‘03 Defender 130 with a Td5 became their home across the continents. Their stories and Graeme’s observations and commentaries on the societies of the world made for engaging reading, and left a nagging sense that a life proscribed by the routine of work, limited geography and supposedly comforting predictability might prove seductive, but hardly fulfilling. And if you fear that world travel with your children might limit their futures, well, read what Graeme and Luisa have to say and it might change your mind.

While Roy and Michelle left comfortable lives and supportive families behind, Graeme and Luisa Bell from South Africa grew up in harsher personal and political circumstances. In his book, We Will Be Free, Graeme recounts the broken family and spurious dreams that were made right by the triumvirate of his marriage to Luisa, the birth of his children, Keelan and Jessica, and their Land Rovers. A much loved Series III and an early Range Rover Classic were simply too small for overlanding with a family of four, but an ‘03 Defender 130 with a Td5 became their home across the continents. Their stories and Graeme’s observations and commentaries on the societies of the world made for engaging reading, and left a nagging sense that a life proscribed by the routine of work, limited geography and supposedly comforting predictability might prove seductive, but hardly fulfilling. And if you fear that world travel with your children might limit their futures, well, read what Graeme and Luisa have to say and it might change your mind.

Should you have a reason to remain anonymous, do not choose a Land Rover. Despite the styling slippage due to increasing fuel economy and safety standards, Land Rover’s styling cues remain rather distinctive—especially the “heritage” Land Rover models favored by enthusiasts. No less an authority than Gordon Murray, the engineering genius behind the McLaren, identified the Land Rover Discovery as “the best SUV ever.” Any Defender, Series, Range Rover Classic or Discovery/LR owner will confirm that their vehicle is rarely, if ever, confused with another marque.

Then there’s rarity. Last year U.S. consumers purchased 16-17 million cars and trucks, of which Land Rover sold 70,582, (their best year ever). That means Land Rover captured .004% of the US market. Save for a very few metropolitan areas, you’re unlikely to see another Land Rover coming and going—certainly not without a wave in return. Indeed, that was the observation of new LR4 owners just yesterday— they remarked, “We’ve driven up and down I-95 a lot and never see another one.”

My ’66 Series II-A and I arrived on this island at the same time 25 years ago. When our boatyard owner first saw it he claimed to have the perfect bumper sticker for me: “My Other Car is a Piece of S___ Too!” He still laughs at it any time I have to cobble together a repair from marine parts. As the only Series Land Rover in daily use, it stands out and its breakdowns [broken shift lever, failed spring plate U-bolt, corroded coil wire, etc.] provoke much mirth among my year-round neighbors. Its occasional failures stand out because, well, a Land Rover stands out.

My ’66 Series II-A and I arrived on this island at the same time 25 years ago. When our boatyard owner first saw it he claimed to have the perfect bumper sticker for me: “My Other Car is a Piece of S___ Too!” He still laughs at it any time I have to cobble together a repair from marine parts. As the only Series Land Rover in daily use, it stands out and its breakdowns [broken shift lever, failed spring plate U-bolt, corroded coil wire, etc.] provoke much mirth among my year-round neighbors. Its occasional failures stand out because, well, a Land Rover stands out.

So when I pulled into line at the island’s only gas pump, I felt dismayed when I turned the key and no warning lamps illuminated, nor did pressing the starter button elicit any sound. I turned on the headlights, stepped outside and saw nothing. The problem had to be at the battery. A quick check with a multimeter showed 12.5v at the posts. I pushed on the battery slightly, got into the car, turned the key, pushed the starter button, and it fired up. I didn’t want to press my luck so I left the Rover running while I filled it up, and then drove home.

So when I pulled into line at the island’s only gas pump, I felt dismayed when I turned the key and no warning lamps illuminated, nor did pressing the starter button elicit any sound. I turned on the headlights, stepped outside and saw nothing. The problem had to be at the battery. A quick check with a multimeter showed 12.5v at the posts. I pushed on the battery slightly, got into the car, turned the key, pushed the starter button, and it fired up. I didn’t want to press my luck so I left the Rover running while I filled it up, and then drove home.

Once out of eyesight of island skeptics, I turned off the car and tried to start it again. Nothing. Over 20 years ago something similar happened and I discovered the problem to be a loose ground from battery to the battery box. This time, the ground cable from the battery (now grounded to the engine block) looked ok, but I removed it and cleaned each end. Upon buttoning everything back up, no change. Finally, I checked the power wire from the battery to the starter switch. It looked tight, but I would wiggle it in place at the battery end. Tightening it down made all the difference—the Rover started right up.

Once out of eyesight of island skeptics, I turned off the car and tried to start it again. Nothing. Over 20 years ago something similar happened and I discovered the problem to be a loose ground from battery to the battery box. This time, the ground cable from the battery (now grounded to the engine block) looked ok, but I removed it and cleaned each end. Upon buttoning everything back up, no change. Finally, I checked the power wire from the battery to the starter switch. It looked tight, but I would wiggle it in place at the battery end. Tightening it down made all the difference—the Rover started right up.

The same vibrations that transmit themselves through my body in my II-A travel through every component in the vehicle. Invariably, some will loosen over time. This episode reminded me of making the time to simply check over every nut and bolt when I do an oil or gear oil change. Perhaps then I won’t embarrass my Land Rover with my shortcomings.