A contemporary Land Rover offers a majestic driving experience, starting with the steering wheel. You have most every comfort feature under your thumb or at your fingertips, from regulating your speed and selecting a gear to initiating a hands-free phone call. It’s different with a heritage Land Rover.

My ‘66 Series II-A features “Steering by Arm-strong,” which explains the whopping 16” diameter size. It also has the “banjo” style spokes, which supposedly offered more road feel. That wheel was replaced in mid-1966, by the more contemporary all-Bakelite, three-spoke wheel. Despite its substantial circumference the rim is surprisingly thin, almost delicate. You tend to drive with your arms extended to shoulder width; your individual girth determines your distance between you and the wheel because the seats don’t adjust at all. Even the “deluxe seats” of the late Series II-A’s and Series IIII’s offered minimal seat adjustment.

I started this column over 20 years ago to celebrate the view and feel from behind that giant wheel, with the belief that the only limits on your Land Rover travels would be your wallet and your courage. As Car and Driver once wrote, “Perfectly reasonable people take leave of their senses upon first meeting the Land Rover. It is less a car than a state of mind.” Children of all ages adore them. Females or males whom you wish to become your significant other demonstrate whether they’re right for the role through their affection for the Series Land Rover or Defender. And yes, you actually must drive these Land Rovers, as they lack every contemporary driver’s assist.

Barbara Moran, a Boston-based science writer, summed this up nicely in a Boston Globe column headlined, “My Car Wants to Drive. I’m Not Interested. This is a Problem.” When looking to replace her worn out car, she discovered that all new cars come with screens on the dashboard and that shutting it down turned off the radio, too, “a cruel bargain.” She felt angry over the lane-sensation feature that nagged you to stay in your lane on the highway, or offered to parallel park the car for her. “I don’t want that,” she snapped at the auto salesman, “Why would anybody want that? Turn it off!” She went on, “I’m sure I appeared ungrateful, which I was. Also resentful, somewhat panicked, and old. I am perfectly capable of staying in the lane all by myself, thank you. I can also parallel park, so you can go ahead and shut off [that feature] while you’re at it.” For Moran, these features begin the “slippery slope to the terrifying world of fully autonomous robot cars.” (Since the self-driving Tesla fatal crash in Florida, I would guess that the 16% of Americans polled who want an autonomous car might decline further.)

She notes, “Learning to drive has always been a rite of passage. Why would anyone gladly give that up? Are these the same people who let Spotify choose all their music?” As she test-drove a contemporary vehicle, she suggested it “sensed my distrust, because it somehow connected to my iPhone and they began to talk to each other. They colluded, offering to show me maps and guide me around traffic jams. Sometimes the iPhone played music on the car radio without asking.” She told her husband, “The car and the phone are talking to each other and I don’t like it.” After Moran bought her new car, her husband rigged it so it can’t talk to her phone anymore. “Now a plaintive message sometimes pops onto the car’s screen: ‘No iPhone detected. Would you like me to connect one?’ No, I would not. I want the vehicle to remember who’s driving the car.”

Funny, but I said something similar when road testing a new Range Rover at Land Rover Richmond (VA) last year. I has sensibly left my phone in my pocket so I would not use it while driving something that costs four times my annual income [in a good year!]. Suddenly a message popped up on the screen identifying my phone and announcing its readiness for me to make a call. For all I know, my phone is still in the Range Rover’s database—no one has called me yet.

I will speak to the seductive quality of bonding between a phone and a Land Rover. Land Rover Charlotte loaned me a new Range Rover Evoque to attend the Old North State’s Uwharrie 2015 last fall. Secretly, my phone and the Evoque started smooching via Bluetooth and I couldn’t help but call Thompson Smith, the magazine’s Art Director, to crow how I’d entered the 21st century. As a card carrying member of the digerati, he was suitably unimpressed.

Every model of a classic Land Rover reminds you of your responsibilities as a driver. The overall noise level of a Series Land Rover when underway renders cellphone calls improbable. And anyone who could text with the vibration level of a Series Rover underneath their fingers should go into microsurgery immediately. Ignore your driving responsibilities for a moment on a crowned, paved road and you’ll be examining the road shoulder very closely. A Series Rover or Defender tends to wander in side winds. While a Discovery or Range Rover Classic might hold the road better, both require attention during sharp cornering, especially if you’ve not replaced the suspension bushings in a while. These coil sprung Land Rovers did come with ABS and electronic stability aids, but they still required that you, the driver, activate them by hitting the brake pedal or turning the steering wheel. For goodness sake, before you run over that child on a bike behind you, you’re expected to turn your head around and check all your mirrors when backing up. That’s why all Land Rovers, hard top or soft top, came with rear windows.

When I bought my Series II-A a quarter-century ago, its Sage Green paint had degenerated into a puke green, kind of like a green T-shirt faded out by numerous washes. I wanted to believe that my Rover’s patina came honestly, maybe by hacking through jungles, extended expeditions or baking in the hot sun during desert crossings. Given that a dealer’s sticker indicated it had spent considerable time in southeastern New England, anything except beach time seemed unlikely and overall neglect probably accounted for its appearance. Indeed, portions of the wing tops had been worn down to the bare Birmabright.

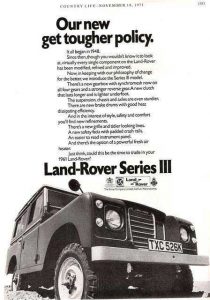

In period, Land Rover promised “car-comfort” with “large windows giving splendid all-round visibility, and with all of them opening so that ventilation can be precisely controlled.” You could “motor all day at a steady 70 mph… on deep-cushioned seats while your feet sit on fitted rubber matting. It’s a nifty parker on a shopping street and a convenient coach to take kids to school in.” Road Test magazine tested a then-new Series III in 1973, and offered this backhanded compliment. “In a rather agricultural way, the standard of finish is good inside and out.” Still, they felt compelled to ponder, “Nobody in their right mind would now buy a Land Rover for ordinary road transport (would they?) for its performance is low and its comfort minimal.”

Driving the II-A exposed me to its “car-comfort” and made me wonder just how many martinis the Mad Men of the advertising department had imbibed for lunch. The “deep-cushioned seats” did not relieve numbness and the ventilation lacked “precise control.” Acceleration was measured with a sundial instead of a stopwatch. Stopping was accomplished with a double-pump dance step. Nonetheless, I took great pride in mine and assumed that its “quirks” represented the driving experience of all Series Land Rovers. Then I visited Rovers North and had Charlie Haigh (a Rovers North tech now living and working in Virginia) drive mine. I hadn’t seen knuckles that white before; when he relaxed his gritted teeth, he adjusted the steering and suggested I should really drive a “sorted out” Series Rover. You see, “They’re not all like that.”

Indeed, his tweak of the steering improved it dramatically. Later in the mid-90s, a Rovers North rebuilt engine replaced the worn-out one that had come with the QE I. Once broken in, its performance sparkled such that I had to pay attention to speed limit signs—no wonder Land Rover claimed their vehicles could cruise at a “steady 70 mph.” I didn’t use a drop of oil between 3,000-mile oil changes. With its upbeat performance, I now wondered about its appearance.

You see I basked in QE I’s perceived glory until I saw a restored one. The paint colors for the “Export” market—pastel green and blue, dark blue, sand or “Masai Red”—made the Land Rover even more majestic. I needed to remember that new car buyers expected lustrous paint and comfortable interiors. Thirteen years ago, the QE I finally received a professional paint job from East Coast Rover and to this day, still has a nice luster when it receives its annual wash and wax. Although used daily for work it still looked good from a distance, say, 25 feet in dim light.

Until late June, that is, when I learned why to use low range when maneuvering a very heavy boat on a trailer down a steep, rock-lined boat ramp. Now the QE I has its first significant dent in the rear tub; time to learn more about aluminum bodywork!