A lot of patrons make wild claims when stepping out of a bar, but this time, the vision of a genuine Camel Trophy Discovery was not an alcohol-induced hallucination.

The brewpub in this instance housed the Graydon Beer Company, Santa Rosa Beach, FL, and it served as the “emergency” gathering place for last April’s 30-A Sand Rover Rally, when heavy rains forced the move from a grassy knoll to a paved location. Asking Land Rover enthusiasts to meet up at a brewpub proved an easy sell.

The brewpub in this instance housed the Graydon Beer Company, Santa Rosa Beach, FL, and it served as the “emergency” gathering place for last April’s 30-A Sand Rover Rally, when heavy rains forced the move from a grassy knoll to a paved location. Asking Land Rover enthusiasts to meet up at a brewpub proved an easy sell.

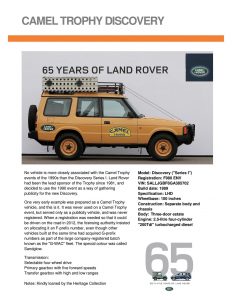

As I walked towards the bar, I spotted a three-door Discovery in Camel Trophy livery. The names of the competitors, Rob Kamps and Stijn Luyx, stood out on the side of the fender; from the Camel Trophy/Worldwide Brands book The Great Adventure, I learned they won the ’90 Camel Trophy. What was this Discovery doing in Florida?

The answer came quickly as John and Karen Bobe, Gulf Shores, AL, wandered over to see who was drooling over their Discovery. John, a real estate broker, received a lead on the vehicle when a friend searched for a Defender 110 to import into the US. “My friend, a Freelander owner, was related to the team members in the Netherlands. When he didn’t want the Discovery, I decided to purchase it. It arrived through the port of Jacksonville around the same time as a hurricane. I was quite relieved that it arrived undamaged.”

The ’90 Camel Trophy took place in Eastern Siberia, starting in Bratsk and heading some 1,000 miles south to Irkutsk and Lake Baikal. The decidedly-untropical locale made sense in the geopolitics of that era. The seemingly monolithic Union of Soviet Socialist Republics was weakening under domestic pressure from its member states, as well as external pressure from the USA and Western Europe nations. With a warming of international relations, the Russian Federation seemed an appealing change to Worldwide Brands.

The ’90 Camel Trophy took place in Eastern Siberia, starting in Bratsk and heading some 1,000 miles south to Irkutsk and Lake Baikal. The decidedly-untropical locale made sense in the geopolitics of that era. The seemingly monolithic Union of Soviet Socialist Republics was weakening under domestic pressure from its member states, as well as external pressure from the USA and Western Europe nations. With a warming of international relations, the Russian Federation seemed an appealing change to Worldwide Brands.

Fred Monsees, Howes Cave, NY, competed with Lea Magee as the US entry in 1990. Fred credits the Dutch team with “navigation and driving skills that were spot on.” He also remembers, “Vodka went a long way to getting things done in Siberia.”

The organizers had chosen a route that largely ran on permafrost, which turned out to be neither permanent nor frosty. “The top layer was thin and underneath lay goo,” Fred recalled. “Supposedly we were on a schedule and you weren’t going to get far when you had to winch for 200 miles. As we fell behind, we had to constantly call out Forestry Bureau workers with their tracked vehicles. We would link up five or six Discoverys and have them tow us out. Since the Russian vehicles often got stuck themselves, they were reluctant to go back to help-out the other teams. And that’s when we learned the importance of vodka.”

The organizers had chosen a route that largely ran on permafrost, which turned out to be neither permanent nor frosty. “The top layer was thin and underneath lay goo,” Fred recalled. “Supposedly we were on a schedule and you weren’t going to get far when you had to winch for 200 miles. As we fell behind, we had to constantly call out Forestry Bureau workers with their tracked vehicles. We would link up five or six Discoverys and have them tow us out. Since the Russian vehicles often got stuck themselves, they were reluctant to go back to help-out the other teams. And that’s when we learned the importance of vodka.”

The organizers quickly regrouped, as it appeared that the event would bog down in the Siberian quagmire. Their response came based on aerial photography that suggested the best route would be through rivers or river beds, in which the ground would be firm. Fred Monsees remembered, “We wanted to minimize the chance of damage from hidden obstacles, so Lea and I took turns sitting on the hood as we waded through three to four feet of water — which was fricking cold.”

Between the WWII-era corduroy roads and the collapsing permafrost, the conditions wreaked havoc with the Discoverys. The three-door Discoverys suffered from collapsing body mounts, which meant the rear door jammed against the rear bumper. Even the Land Rover 130’s, brought along as supply and support vehicles, ran into problems as their heavy weight conspired with the conditions to literally bend their axle casings (future events would see parts and supplies shared between each of the competing Land Rovers). It also demonstrated the value of a four-door Discovery for off-roading. “Gary Wescott was the journalist who rode with us,” Fred said, “and getting him and our gear in and out of two-door was a pain.”

Between the WWII-era corduroy roads and the collapsing permafrost, the conditions wreaked havoc with the Discoverys. The three-door Discoverys suffered from collapsing body mounts, which meant the rear door jammed against the rear bumper. Even the Land Rover 130’s, brought along as supply and support vehicles, ran into problems as their heavy weight conspired with the conditions to literally bend their axle casings (future events would see parts and supplies shared between each of the competing Land Rovers). It also demonstrated the value of a four-door Discovery for off-roading. “Gary Wescott was the journalist who rode with us,” Fred said, “and getting him and our gear in and out of two-door was a pain.”

The US team’s strategy focused on keeping their Discovery, with its wondrous 200 Tdi engine, intact, so they could excel on the special stages planned for the event’s last days. “We installed new shocks just before the scheduled stages,” Fred noted. “We’d been lucky not to suffer tire failures, so we could replace our front tires with fresh ones.” Then, confronted with too much lost time within the 19-day schedule and the carnage to vehicles inflicted by the conditions, the organizers cancelled the special stages. However, they had not forgotten Fred and Lea’s off-roading skills; both were asked to drive support vehicles in the following year’s event in Tanzania-Burundi.

The US team’s strategy focused on keeping their Discovery, with its wondrous 200 Tdi engine, intact, so they could excel on the special stages planned for the event’s last days. “We installed new shocks just before the scheduled stages,” Fred noted. “We’d been lucky not to suffer tire failures, so we could replace our front tires with fresh ones.” Then, confronted with too much lost time within the 19-day schedule and the carnage to vehicles inflicted by the conditions, the organizers cancelled the special stages. However, they had not forgotten Fred and Lea’s off-roading skills; both were asked to drive support vehicles in the following year’s event in Tanzania-Burundi.

John Bobe reflected on his good fortune. “I didn’t know how few Camel Trophy vehicles there were until recently. I’ve also recently purchased a Land Rover 110 from the 1988 event [Sulawesi, Indonesia]. Sadly, the frame is completely rotten and unsalvageable, so I’ve ordered one from Rovers North. The next challenge is the 2.5 diesel engine, which really feels underpowered for today’s traffic. I hate to change the vehicle, but I might have to replace the 2.5 with a 200 Tdi.”

John Bobe reflected on his good fortune. “I didn’t know how few Camel Trophy vehicles there were until recently. I’ve also recently purchased a Land Rover 110 from the 1988 event [Sulawesi, Indonesia]. Sadly, the frame is completely rotten and unsalvageable, so I’ve ordered one from Rovers North. The next challenge is the 2.5 diesel engine, which really feels underpowered for today’s traffic. I hate to change the vehicle, but I might have to replace the 2.5 with a 200 Tdi.”

He’s also been in contact with other Camel Trophy enthusiasts, such as Peter Sweetser in Florida and Connor Davis in Colorado, and through them, “I realized that I have some original treasures of Camel Trophy items here in my office. I do plan on going through all the stuff that came with my Camel Trophy vehicles and cataloging them.”

As a reminder of the tortuous conditions in Siberia, John recently took his Discovery to a friend’s shop for a wheel alignment. “We both laughed as we looked at the bent sections underneath the Discovery. ‘I’m really not sure what to do with this,’ he said.”