Social media programmers know what clickbait works on different people. As a single guy, I’m amazed at how many seductively-posed women request that I accept their Facebook friend request, ask to chat with me or message me on Instagram.

Phooey. If you really want to know what will stoke my emotions and take action, show me a Series Land Rover — the rattier the better. Ask Ralf Sarek and Ben Shelton of Sarek Autowerke, Glen Ellen, VA. They exploited this emotional reflex — shamelessly — when I visited their specialist shop after the MAR last October.

Phooey. If you really want to know what will stoke my emotions and take action, show me a Series Land Rover — the rattier the better. Ask Ralf Sarek and Ben Shelton of Sarek Autowerke, Glen Ellen, VA. They exploited this emotional reflex — shamelessly — when I visited their specialist shop after the MAR last October.

The lot at Sarek featured some stunning examples of Land Rovers. I was besotted by a ’91 two-door Range Rover that came from Portugal with a VM diesel engine. It sounded gloriously lumpy, a real old school diesel. A custom touch by Sarek saw an LT77 5-speed supplant the original transmission. Just seeing those vertical door handles again made me sigh. Opening the door revealed the brilliant David Bache rectangular fascia and instrument pods that remained a hallmark of the Range Rover Classic. The cloth interior had that mock mouse fur-corduroy look and feel.

Near it sat a Discovery II G4, gleaming in its Tangiers Orange-black-blue livery. Only 200 were manufactured in 2004; standing beside this one tripled the number I’ve ever seen to three. A Series III 109” in a soft blue graced my eyes, clearly aware of its near-cherry condition. What was the silver-gray Discovery II with Vermont plates doing in Richmond, VA? It even had, appropriately, a Rovers North decal on it!

Near it sat a Discovery II G4, gleaming in its Tangiers Orange-black-blue livery. Only 200 were manufactured in 2004; standing beside this one tripled the number I’ve ever seen to three. A Series III 109” in a soft blue graced my eyes, clearly aware of its near-cherry condition. What was the silver-gray Discovery II with Vermont plates doing in Richmond, VA? It even had, appropriately, a Rovers North decal on it!

Thankfully I didn’t see a “For Sale” sign on any of them, but honestly, their stunning conditions allowed me to hold back. As befits my appearance, I prefer the “lived-in” or “worn out” look.

Then, before me, stood the kind of 109” that hard-bitten experts deem “dilapidated,” but romantics like me consider “patinaed.” I felt like I needed a tetanus shot from just breathing the air next to it. This 109” screamed “parts car” to knowledgeable enthusiasts, but to me, it whimpered like a lonely puppy at a shelter lifting its big eyes and imploring, “Take me home with you.”

Then, before me, stood the kind of 109” that hard-bitten experts deem “dilapidated,” but romantics like me consider “patinaed.” I felt like I needed a tetanus shot from just breathing the air next to it. This 109” screamed “parts car” to knowledgeable enthusiasts, but to me, it whimpered like a lonely puppy at a shelter lifting its big eyes and imploring, “Take me home with you.”

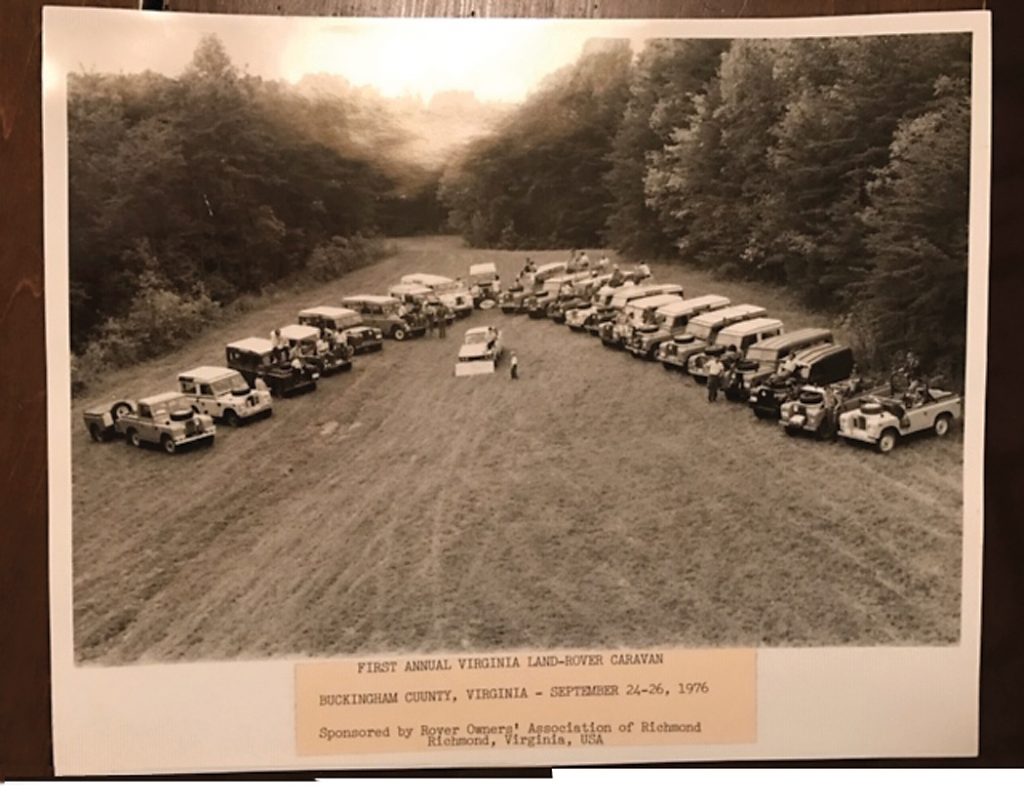

Ralf and Ben knew they had a live one, so they played the card used routinely to raise funds for starving children. “This ’67 109” attended the very first MAR in the 1970s. Its owner was one of the founders of the Rover Owners of Richmond, which later became the Rover Owners of Virginia. It is still owned by the same family. They’re really torn as to what to do with it.”

The absence of a motor and transmission should have given me pause, as should the bulkhead rust and an interior that looked like a scene from “Twister.” Ralf and Ben assured me “it’s all there” amidst the jumble of parts inside the Rover, and that if someone could actually convince the family to sell the 109”, they had a plan to refurbish it in time for MAR 2019. To add drama and emotional impact, their eyes welled up and their lips trembled as they envisioned their dream coming to fruition.

As they knew I would, I bit — hard. In the words of David Short, the president of ROAV, “Thank God you bought it. I thought I would have to do it!” You’re welcome, David.

Series Land Rovers appeal for many reasons, but one stands out field repairability. As Land Rovers were exported to hundreds of countries right from their start, Solihull assumed that owners in distant lands would perform their own maintenance and repairs without the benefit of shop accouterments like lifts or air tools. This approach continued with the early Range Rover Classics, Defenders and Discovery I-II’s, but with a caveat. My Series I shop manual, in four languages, is ½” thick, the same as my Series II-III Haynes Manual. My Discovery I [MY ’95-’99] Workshop Manual, in English only, is three times as thick.

I pulled it out when Gilroy, my ’97 Discovery I, passed its annual Maine state inspection with an admonition that I should replace the front brake pads — stat. The mechanic’s instincts from looking at the brakes and overall experience with neglected disc brake systems led him to recommend I get a set of calipers, or a rebuild kit — just in case. He also announced resolutely that he would not have time to do the work.

I pulled it out when Gilroy, my ’97 Discovery I, passed its annual Maine state inspection with an admonition that I should replace the front brake pads — stat. The mechanic’s instincts from looking at the brakes and overall experience with neglected disc brake systems led him to recommend I get a set of calipers, or a rebuild kit — just in case. He also announced resolutely that he would not have time to do the work.

The order went out to Rovers North for disc pads, calipers and lug nuts. January is a cold month in Maine to work outdoors, but I lucked out when I mooched garage space inside our electric co-op’s storage building. Naturally, since I had the new lug nuts on hand, the old ones came off without a hitch. A glance at the pads confirmed his recommendation; very little brake lining remained. I removed the pins that held the pads to the calipers, but as predicted, the caliper pistons seemed reluctant to move. I called upon cans of penetrating oil and brake cleaner, sprayed liberally, opened the bleeder screw, maneuvered the piston with pliers and eventually pushed all the pistons back sufficiently to insert the new pads (I’ll hold onto the new calipers for future use.) I inserted the tensioning springs over the new locating pins, slid them into place and locked them in with new cotter pins. I tightened up the bleeder screw, checked the fluid level again, and pumped on the brakes. They settled in quickly.

For skilled mechanics, changing out pads is a yawn. I know this because it takes up only a quarter-page of the 500-plus pages in the workshop manual. For me, it’s worth a high five, not because of its [relative] challenge, but because I could do it properly myself. Field maintenance and repairability have always been hallmarks of Land Rover ownership — and a reason for concern given the increased complexity of contemporary Land Rover models.

Sadly, the ever-growing list of required features for all new vehicles adds complexity and cost to the simplest maintenance. Replacing a sealed beam headlight on my Series IIA involves a few tiny screws and a three-prong connector. The earlier Range Rover Sports used a Xenon bulb and replacement is more fiddley. The new Range Rover features “Pixel LED headlights comprised of a beam of 144 LED’s” that automatically shadow themselves to illuminate the road while reducing glare on oncoming traffic. As your driving speed increases, an optional “laser supplementary high beam” adds another 1,600 ft. of visibility. I think these new features are amazing, but if something goes wrong, they’re out of my league as a mechanic.

Driving your own Land Rover every day is a 10. As Spinal Tap’s Nigel would have said, driving someone else’s nicer Land Rover is an 11.

I love the feel of the thin rim, banjo steering wheel of my Series IIA. The wheel houses only a horn button, no airbag, cruise control, entertainment system and cellphone buttons. Of course, that also means I must drive more carefully, entertain myself and wear headphones for hands-free cellphone use.

For those features, I must turn to my personal 11, an ’06 Range Rover Westminster, one of 250 produced that year. Unlike the relic I recently purchased, this gem belongs to Bob Steele, Richmond, VA, one of several Land Rovers in his family. A former president and active member of ROAV, Bob has kindly loaned me this unique Range Rover model for the 235-mile, 3.5-hour drive to Pembroke, VA, the site of the MAR. Zero-sixty mph in my Series IIA was a leisurely 36.1 seconds when new, and I doubt it’s gotten any quicker. Zero-sixty in the Westminster was 6.7 seconds when new, and it feels even faster with its 175,000 miles on the motor. It’s speed at the end of a quarter-mile could be 95 mph. For my IIA, the quarter-mile would require 25.7 seconds; it’s speed at the end would also be its top speed of 73 mph.

My 11 cossets me in Range Rover comfort, whether at 75 mph on-road or 7.5 mph off-road. Time to crank up the volume!