Land Rover and Africa go together seamlessly and both have played major roles in my family history.

Like many Scots before him, my grandfather William immigrated to the USA, met his English wife in Chicago, and returned to England in the 1930s, to escape the Depression. At the beginning of WWII, the family returned to the US. From there he graduated from seminary and in 1948, they served as missionaries in the former “Gold Coast,” now Ghana. From 1948-75 he drove all over West Africa, long before anyone considered it “overlanding.” After retiring, they lived in Edinburgh for 10 years and then Merseyside, England, for 10 years.

Like many Scots before him, my grandfather William immigrated to the USA, met his English wife in Chicago, and returned to England in the 1930s, to escape the Depression. At the beginning of WWII, the family returned to the US. From there he graduated from seminary and in 1948, they served as missionaries in the former “Gold Coast,” now Ghana. From 1948-75 he drove all over West Africa, long before anyone considered it “overlanding.” After retiring, they lived in Edinburgh for 10 years and then Merseyside, England, for 10 years.

My father, also named William, was born in Manchester, but he grew up in Ghana, returned to the US for college, married my mum, Lois, and they went to Mali as missionaries from 1956-75. I grew up in Mali, where we lived in the village of Niafunke, on the edge of the Niger river, bordered on the north side by the Sahara. Niafunke was a hundred miles or so from the fabled city of Timbuktu. I visited there often as it served as our mission headquarters.

Over the years the family drove a Citroen 2CV, Peugeot 404, Dodge Power Wagon, but none  lasted like our Series Land Rovers. Our first was a ’67 Series IIA 109”, and in 1970, we purchased a Series III 109” diesel direct from Solihull and had it shipped to Abidjan (Ivory Coast). In those British Leyland days, it came with a leaky gas tank; we had to find a replacement before going up country to Bamako (Mali) and on north to our home on the edge of the Niger River.

lasted like our Series Land Rovers. Our first was a ’67 Series IIA 109”, and in 1970, we purchased a Series III 109” diesel direct from Solihull and had it shipped to Abidjan (Ivory Coast). In those British Leyland days, it came with a leaky gas tank; we had to find a replacement before going up country to Bamako (Mali) and on north to our home on the edge of the Niger River.

There was no electric service, other than the odd government generator, for hundreds of miles from the city. For our first 12 years, we lived in a mud house with a thatched roof. A government radio telephone line provided our only communications, but often, it would fail when drifting sand dunes would elevate the surface so camels could stretch and chew up the lines. We finally bought a small Onan generator to provide a few hours of evening light.

We hunted, fished or grew everything we ate. Once or twice a year we would make it down country by road or on the Niger River and bring back provisions. One of my favorite memories included a weekly square of chocolate and sip of Coca Cola. Every four years we would bring back dry goods from America. At times, our fuel would come contaminated, like when it caused our kerosene-powered refrigerator to explode and almost took my mother’s life. It necessitated an emergency night trip across the untracked desert to Timbuktu (we got lost), and then evacuation down country for medical attention.

We hunted, fished or grew everything we ate. Once or twice a year we would make it down country by road or on the Niger River and bring back provisions. One of my favorite memories included a weekly square of chocolate and sip of Coca Cola. Every four years we would bring back dry goods from America. At times, our fuel would come contaminated, like when it caused our kerosene-powered refrigerator to explode and almost took my mother’s life. It necessitated an emergency night trip across the untracked desert to Timbuktu (we got lost), and then evacuation down country for medical attention.

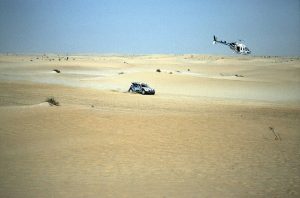

Beginning in 1960, we children went off to boarding school where we stayed eight to nine months before returning home for three months (I was the oldest and first to go.) We had during the 1000-mile journeys to/from school, first in Mamou, in the highlands of Guinea and later Bouake, Ivory Coast. A visit to my grandparents meant trips to Ghana; other treks took us to Upper Volta, Niger, Senegal, or down to the capitol city of Bamako for supplies. The Paris-Dakar race used to pass very close to Timbuktu. My brother would go out along the route and scrounge spare parts from the teams (motorcycles or vehicles were abandoned where they broke down.)

The Niger River’s water level varied based on the season, blocking access to Timbuktu. You could travel along the north side of the river through the desert, or cross the river to roads on the south side. A trip along the north/desert side required use of a compass, and/or following tracks left by the desert patrols, or the occasional “Overlander.” Depending on the time of year, the Niger river can flood far north into the grasslands; at times, we had to divert into Mauritania to avoid the flooding.

The Niger River’s water level varied based on the season, blocking access to Timbuktu. You could travel along the north side of the river through the desert, or cross the river to roads on the south side. A trip along the north/desert side required use of a compass, and/or following tracks left by the desert patrols, or the occasional “Overlander.” Depending on the time of year, the Niger river can flood far north into the grasslands; at times, we had to divert into Mauritania to avoid the flooding.

More than once we found ourselves stuck and stranded when hazarding into flooded areas hidden by the tall grass. Once, we sank in up to the axles. My father walked in search of help (something he had done several times over the years and it almost cost him his life more than once.) He finally came across a camel caravan that took him into town to get help. Mom and us kids stayed the night in the bush and could hear the wild animals circling us all night. We saw the circle of trampled earth tracks 100-foot out around our camp the next morning. The next day, I climbed a thorn tree and amazingly a desert patrol spotted me and pulled us out. (They said they thought the site of a white creature in a tree in the middle of nowhere was a demon.) When Dad returned with help a day later, he found us on dry land waiting for him. In the next town, residents told us they had been searching for a “mad elephant” that had been destroying villages in the area.

More than once we found ourselves stuck and stranded when hazarding into flooded areas hidden by the tall grass. Once, we sank in up to the axles. My father walked in search of help (something he had done several times over the years and it almost cost him his life more than once.) He finally came across a camel caravan that took him into town to get help. Mom and us kids stayed the night in the bush and could hear the wild animals circling us all night. We saw the circle of trampled earth tracks 100-foot out around our camp the next morning. The next day, I climbed a thorn tree and amazingly a desert patrol spotted me and pulled us out. (They said they thought the site of a white creature in a tree in the middle of nowhere was a demon.) When Dad returned with help a day later, he found us on dry land waiting for him. In the next town, residents told us they had been searching for a “mad elephant” that had been destroying villages in the area.

Experiences like this were common place for our travels in those days. On one occasion, Dad was very near death when villagers found him on the outskirts of town. Mom and us kids were left with the truck, hoping our food and water didn’t run out, and never sure if Father would make back. I remember being 6-years-old, in the desert, with a heat stroke, almost out of water, and waiting for Dad to get back (that’s the time he almost died, and if he had, no one would have known where to look for us).

Experiences like this were common place for our travels in those days. On one occasion, Dad was very near death when villagers found him on the outskirts of town. Mom and us kids were left with the truck, hoping our food and water didn’t run out, and never sure if Father would make back. I remember being 6-years-old, in the desert, with a heat stroke, almost out of water, and waiting for Dad to get back (that’s the time he almost died, and if he had, no one would have known where to look for us).

All travel required provisions of water, fuel, sand tracks, tires and as many spare parts as you could load. It wasn’t uncommon to break springs, axles or drive shafts. Often you would get bad gas. Poverty meant spare parts could be unaffordable, so you would stuff the tires with straw when tubes could no longer be patched. Twice we cracked windshields because of the heavy weight on the roof racks. Travel by way of the river involved either river crossings in shallow water, crossing on ferries, or travel by river barge down the Niger to Mopti. Once past the desert, travel in the rest of West Africa was on dirt, generally washboard roads, and often involved stopping to repair bridge crossings, many river crossings and many check points (especially during the West African “Communist” era of the 60s when westerners were suspect.) The dangers of travel in those days weren’t limited to the roads.

Far from Africa, in Florida I sought to rekindle those memories by purchasing a ’67 Series IIA NADA 109”. Its 6-cylinder engine with the Westlake head was intended to give a 109” more power for the North American market. My 109” required a new frame and many more parts from Rovers North. Shortly before his death in 2017, my father visited and joined me in a trip down memory lane. I enjoyed seeing the pleasure he took from riding in a Land Rover again. We went on a ride together to a local off-road event and on the way back broke down at night, in the middle of nowhere. What’s a trip down memory lane in a Land Rover without a breakdown?

Far from Africa, in Florida I sought to rekindle those memories by purchasing a ’67 Series IIA NADA 109”. Its 6-cylinder engine with the Westlake head was intended to give a 109” more power for the North American market. My 109” required a new frame and many more parts from Rovers North. Shortly before his death in 2017, my father visited and joined me in a trip down memory lane. I enjoyed seeing the pleasure he took from riding in a Land Rover again. We went on a ride together to a local off-road event and on the way back broke down at night, in the middle of nowhere. What’s a trip down memory lane in a Land Rover without a breakdown?