Sometimes it just happens. Your dog, on whom you’ve lavished so much love and affection, just had a bad day and snaps at you. The QE I, my ’66 Series IIA 88” SW, has exhibited that very behavior.

Last fall, clearly annoyed by the presence of its stablemate, my ’97 Discovery I SE7, it decided to render its transmission inoperable. With the help of friends, I installed a rebuilt transmission from Rovers North [see Fall 2018 issue -ed.] Then it sleeted, snowed and rained for several months all over my shade tree “garage.”

When weather permitted me to continue the repair, the QE I decided I’d not paid penance and that the exhaust system should rust out and require replacement. Once I removed the intermediate pipe, muffler and tailpipe, I discovered that the threads on the exhaust manifold studs had rusted and worn so badly as to also require replacement. Corrosion meant they would defy this.

A couple of days later, large boxes arrived from Rovers North. Aside from a new exhaust system — this time in stainless steel — I purchased a new exhaust manifold and gasket. Since the exhaust and intake manifolds bolt together, I was saddened — but not surprised — when I could not separate them despite massive amounts of PB Blaster. Cue Rovers North for an intake manifold, gasket, and while you’re at it, a fixing kit with all the bolts and wings for the intake and exhaust manifolds.

A couple of days later, large boxes arrived from Rovers North. Aside from a new exhaust system — this time in stainless steel — I purchased a new exhaust manifold and gasket. Since the exhaust and intake manifolds bolt together, I was saddened — but not surprised — when I could not separate them despite massive amounts of PB Blaster. Cue Rovers North for an intake manifold, gasket, and while you’re at it, a fixing kit with all the bolts and wings for the intake and exhaust manifolds.

The upper row of bolts and studs along the intake manifold went on easily, but the three along the bottom row required the body elasticity of Elongated Man and X-ray vision of Superman — or the time to remove the driver’s side wing. I had neither superpowers nor time, so standing on a log, bent over the wing, my arms folded under the manifold, eventually and in great pain, I managed to start the bolts and ratchet them in place. I hobbled around like Quasimodo for the rest of the day.

Once completed, I could finally install the new header pipe — that is, once I could figure out just how the multiple bends in the pipe could wend their way through the space beside the transfer case under the frame. That required the use of my Hi-Lift jack and jack stands to elevate the IIA sufficient to provide the necessary clearance.

After checking the ignition points, I fired up the motor and enjoyed a gentle burble instead of a raucous BLATTTTT. Once I filled the gas tank, it promptly began to leak — a lot. That required breaking out the Sawzall for the rusted-out bolts. (You’d be surprised how much crud accumulates on your Series’s frame when you don’t power wash it.) The tank rust would result in lacerations to my left arm. Out came the angle grinder to sand off now-visible rust (the grinder died midway through the task) followed by some spray paint. With the use of a trolley jack, I forced the fuel filler and vapor hoses onto the new tank (additional injuries followed) and I swapped out the fuel gauge sending unit. Once screwed into place, the sending unit has refused to work, despite my best efforts at a repair.

The QE I wasn’t done yet. The Land Rover started easily and idled nicely, but after a few days, it surged under load and would occasionally stall out at a stop sign. Off came the top of new Weber to expose the fuel bowl, and sure enough, I spotted plenty of dark grit. Spraying out the jets and the bowl cleaned things up properly, restoring the idle, but retaining the surging. Crawling underneath, I shone a flashlight at the fuel pump glass bowl. It looked like a parfait dessert instead of a double shot of gin. Pumping crud into the carburetor probably didn’t promote smooth running. Maybe the QE I’s hissy fit is over for now.

Paul Mronzinski leaned out of a window of the one antique shop on this island to introduce me to a visitor from the UK. That’s how I met Josh Willis, a Land Rover enthusiast from Ashford, Kent. Josh grew up watching and working with his father, Mick, who repairs, refurbishes and restores Land Rovers in his workshop. His most recent restoration was of a lovely Series IIA 88”.

Josh has set up his own business, JW Minis, to keep original Minis on the road, but he keeps his hand in the Land Rover world. With his father’s help, he revived a handsome Range Rover Classic and continues working on getting his Series III on the road. Josh demonstrated a very British reserve and diplomatic politeness about the condition of my Land Rovers, the QE I and Gilroy, the ’97 Discovery I SE7.

“We live in the country,” Josh said, “with a lot of farmers and horse people. Discoverys with 200 and 300 Tdi’s were very popular. Interestingly, my Dad would be offered Range Rover V8’s for next to nothing, with requests to convert them to diesel or LPG. Now he’s being asked to revert them back to their original motors!”

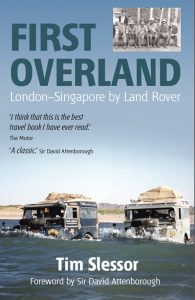

Adam Bennett’s restoration of the London-Singapore Series I and recreation of the storied trek prompted me to treat myself to a copy of Tim Slessor’s First Overland; London-Singapore by Land Rover. I’m embarrassed to admit I’d never read it, and upon completion, rather annoyed at myself for waiting this long.

The 32,000-mile, “Oxford and Cambridge Far Eastern Expedition” left in September 1955, and returned in March 1956. Teammate Adrian Cowell had helped plan a trans-Africa expedition only the year before, but his undergraduate status rendered him unable to participate. So determined was he that this one would come off that he approached Land Rover to supply two new vehicles, Series I 86” Station Wagons, for this expedition. He took the train to the Rover Company offices in Birmingham and two days later reported, “Well, we’ve got them.” Tim Slessor wrote, “Those were some of the best words I had heard.”

Reading the book should humble Land Rover enthusiasts who cower at the idea of undertaking a long trip in their Land Rovers. Slessor reminds us of the enormous efforts undertaken to secure sponsors, plan an itinerary, get visas, research routes (no Google maps or WAZE), communicate by snail mail, and rely on fate and resourcefulness. Finances dictated the need to complete their own auto repairs, but they were continuously delighted by the graciousness and hospitality of strangers, regardless of their station in life.

Reading the book should humble Land Rover enthusiasts who cower at the idea of undertaking a long trip in their Land Rovers. Slessor reminds us of the enormous efforts undertaken to secure sponsors, plan an itinerary, get visas, research routes (no Google maps or WAZE), communicate by snail mail, and rely on fate and resourcefulness. Finances dictated the need to complete their own auto repairs, but they were continuously delighted by the graciousness and hospitality of strangers, regardless of their station in life.

His descriptions of the landscape, people and cultures that he encountered make for a remarkable read. Above all else, he appreciated the team’s Land Rovers. “Although we tested several components of our cars to destruction, we are agreed that if ever we repeated the journey we should not hesitate to take Land Rovers again. The Land Rover, with one or tow modifications, fitted the bill almost exactly. It is a first-class vehicle.”

Jerry LaBant of Liverpool Motorworks, Liverpool, PA, sets up shop at every year’s British Invasion event in Stowe, VT. His collection of original shop manuals, driver handbooks, promotional material and driving accessories from decades past provides a veritable museum of British automotive paraphernalia. It’s through him that I’ve purchased a “Leyland Cars Land Rover – Range Rover Options, Special Equipment and Accessories” Three Ring Binder, a 1974 Optional Equipment Parts Catalogue, and a Series III Sales Brochure — why, I still don’t know as I don’t own either a Range Rover or a Series III.

Land Rover purchases are not made by the mind, but by the heart, and I fell hook, line and sinker for a totally unnecessary Land Rover mechanical pencil — complete with a tiny Series Land Rover floating in mineral oil. Tilt the pencil and the Land Rover floats to the appropriate end. Useless, an “Ant-Man” or “Honey I Shrunk the Kids” moment — but I love it.