Ever since the evolution of Rovers Cars Limited from Rover Cycles in 1903, Rover had always been a small innovative company. This enabled the company to change its direction to suit the ever changing needs of the motoring public. The vast array of notable people that have passed through the doors of its factories first in Coventry and later at its current locale in Solihull is staggering. Their vision of and for the motoring needs of theirs and future motorists is truly remarkable.

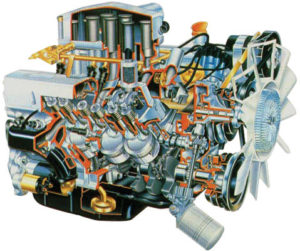

Examples of the longevity of products designed and built at Rover include the LT76 Gearbox, dating from the 1930s, which was still in production at the end of the Series III run in 1983. The V8 Rover engine, bought under license and developed from the Buick V8 in 1963, was still being used in the Discovery II at the end of its production in 2004, albeit with some major modifications!

After the Second World War, in the 50s and 60s, the British motor vehicle industry, like most of British industries in general, was in poor condition. There were several reasons for this — nearly all the medium to heavy industry factories had been built in the 20s and 30s. Many had not survived the bombings from the Second World War. The main government directives for British industries was to export their products. There was a general shortage of steel, though a ready supply of aluminum from war surplus aircraft, leading to Rover cars and Land Rover vehicles using as much “Birmabright” alloy as possible.

The social unrest due to many years of food rationing and general austerity lead to all funds for expansion being hard fought for. Former countries of the British Empire being granted independence and citizenship in the UK created competition for already limited resources. The investment was not being put into new modern factories whereas Germany, France, and Italy were all receiving rebuilding funds. The Labour movement was becoming increasingly powerful, as workers demanded better working conditions. The class structure between the working-class, middle-class, and upper class were starting to be less clearly defined in post-war Britain.

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, Rover Cars still used the assembly lines styled on the methods of the 1930s and 1940s, even though they were working from a newly built factory. To survive the threat of cheaper imported cars, first from Italy, Germany, and France and then from the bigger threat of Japan, the decision was made in 1966, by the boards of Jaguar and Rover Cars, to pool resources. This led to a takeover by British Motor Holdings (BMH). Sir William Lyons, Chairman of Jaguar, was on the BMH Board of Directors, so the lion’s share of funding went to Jaguar.

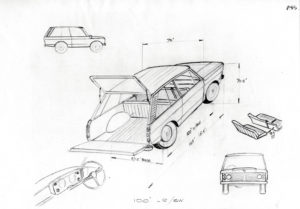

Spen King was in charge of New Vehicle Projects, the “Think Tank” for future vehicles at Rover and then Land Rover, who envisioned a farmers’ working vehicle as well as a recreational vehicle. Rover Cars continued, buoyed by the continuing successes of both the Series Land Rover and the Rover 2000 (P6), both market leaders and innovators for their time. Never satisfied with the status quo, the boffins at Rover Cars could see the need for a luxury 4×4 Station Wagon, a niche that the Land Rover Series vehicle was never able to fill. The first attempt in the 1950s, the Road Rover, never saw traction with the upper management of Rover Cars. In retrospect, the seeds that had been sown would bear fruition in due course. Road Rover wasn’t “luxury,” it was just a bit more car-like than Land Rover, using much of the P4 car body design.

The late 1960s were a busy time for the engineering and design departments of Rover Cars and Triumph Cars (now a division within BMH). 1968 saw the introduction of a designed for Ministry of Defense vehicle, the 88-inch Air Portable, which utilized parts mainly from the stock Series IIA Land Rover bin. The obvious difference was the especially narrow body work, thus enabling the Rover to be flat-packed and loaded on a stock pallet in the C130 Hercules Aircraft. It was designed to keep weight down (hence Lightweight) so that it could be airlifted by the helicopters then in military service. It had to be narrow enough to get into the RAF transport aircraft of the time.

At Triumph, the Triumph Innsbrook, AKA Triumph 2000, morphing into the Triumph 2500, needed a sporty upgrade. The Triumph Stag was the end result. Designed to compete with the German sports cars of the day, the main faults were the Triumph designed V8 engine and poor-quality build. It is remarkable that so many of these Triumphs have lasted to this day, though many have been converted to the superior Rover V8 engine.

If only company politics had not gotten in the way, production would have lasted longer, though Rover Cars were selling every V8 they could build.

Continuing on from Rover Cars and Land Rover joining BMH in 1966, and evolving into British Leyland Cars in 1968, the Range Rover was going through its final design stages and it was found that the Land Rover suspension, steering, and brakes would not be suitable for the proposed bodyweight and V8 engine. The idea was from the start to make a Land Rover with better on-road dynamics — more power (V8), better brakes (all-around disc brakes), and better driver/passenger comfort (coil suspension).

At this time Land Rover was developing for a military contract, the 101 Forward Control Gun Tractor, which was also to be V8-powered. A unique gearbox (the LT95) was developed for the 101 Forward Control and grafted into the Range Rover, as it was felt this was far more suitable than the Land Rover Series LT76 transmission that was available at that time.

During the development of the Range Rover, several 4x4s were purchased from the USA. It was felt this was a large, untapped market for Britain. Across the Atlantic the leisure market was starting to expand. With many new Interstates having been built by 1963, joining most cities with the great outdoors, the potential for a quality, comfortable highway and off-road vehicle was very apparent. The manufacturers of International Scout, Jeep Wagoner and Ford Bronco had also developed 4×4 Station Wagons, as they could see the need in this expanding market. Some of these were purchased by Rover for evaluation, though the Bronco front suspension turned out to be unsuitable for the Range Rover design. I believe not much made it from these vehicles into the final Rover product. The folks at Rover Cars felt they could make a more comfortable and enduring vehicle.

The Range Rover was eventually launched in June 1970. It had always been intended for the Range Rover to be introduced into the USA market. An article in Road and Track dated September 1970, told of a proposed USA launch in mid-year 1971, with options such as tinted glass, AC, and if ready in time, fitted with an auto transmission. The Chrysler TorqueFlite A727, the sturdiest auto box on the market at the time, had been earmarked for installation, though it was a further 10 years before it was offered as a factory option.

Rover cars, including LR, were the only part of BL making a profit at this time, with profits being siphoned off to support the troubled Austin Morris Volume Car Division. The lack of funding for Rover cars and increasing regulations for smog and safety lead to BL including Rover Cars, withdrawing from the US market in 1974.

None the less, a steady trickle of grey market Range Rovers were imported by Automotive Compliance Inc. (ACI), Harbor City, California, amongst others also importing them. ACI imported Range Rovers from UK dealers, making them smog compliant by fitting a three-way catalytic converter and Air Injection pump and charcoal canister, to capture evaporated fuel. As these vehicles were used, not imported, by the manufacturer, the regulations were more lenient and less expensive than if the manufacturer imported direct. With the elimination of the center silencer and the install of the catalytic converter, a more enhanced V8 “rumble” was achieved. ACI estimated there was a 10% loss of power by installing the cats. On the East Coast, Aston Martin Lagonda, Greenwich, Connecticut, advertised both two and four-door models in 1984.

James Taylor, UK Roverphile, has written and generously given me permission to use the following information:

“As the various component companies within BL were brought under more centralized control, finances were centralized. So although the Range Rover was selling strongly and bringing in big profits, those profits were ploughed into a central fund, which was allocated around BL companies, according to their needs. The loss-making Austin-Morris Volume Cars Division had the greatest need and as a result there was very little to plough back into improving Range Rovers. It meant that there was almost no money to develop the model further for the rest of the 1970s.

As 1974 drew to a close, BL ran into a cash flow crisis and turned to the Government for help. The Government responded by partially nationalizing the company and immediately asked industrial advisor Don Rider to look into BL affairs and to make recommendations. The Ryder Report was published in 1975, and among its recommendations was that an independent business unit should be created to look after Land Rover and Range Rover. Although a great deal of the Ryder Report was later rejected, this recommendation was adopted in 1978, and Land Rover Limited was established as an independently managed company within British Leyland. British Leyland’s identity changed over the next decade to Austin-Rover in 1982, to the Rover Group in 1986, and from 1989, the Rover Group and Land Rover with it became the property of British Aerospace, but Land Rover Limited remained unchanged until 1994. In March that year, when the Rover Group was sold to the German BMW Car Company, the first generation Range Rover was still in production.”

The mid 70s saw my own introduction to the Land Rover in the civilian world, from learning to drive in clapped out Series IIAs (Rover MK8) to the spanking new, at that time, Series III Air Portables, plus Bedford RL’s and TL’s. I had left Her Majesty’s Armed Forces, having seen many Land Rovers across the globe being driven, airlifted and dropped (most with complete success — some not.)

One of my military colleagues told me of this new vehicle his father had bought to take their sheep to market, a Tuscan Blue Range Rover. It had manual steering, and an austere interior. It did the job it was bought for though, unmatched by anything else that was available at the time.

To follow on from the partial success of CKD (Complete Knock Down) Series Vehicles, early Range Rovers were bolted together and therefore were ideal to be flat-packed, with engines, axles and gearboxes being supplied ready to assemble in territory. The import duty of countries such as Costa Rica, Venezuela, Australia and Malaysia were upwards to 300% of invoice value. Plus, as the Range Rovers were being assembled in territory, local skilled labor could be used along with local content, such as tires, hardware and in some instances, glass, to keep costs to a minimum. To date I can find no accurate figures of how many Range Rovers were shipped to each country. Maybe someone out there has further data or pictures of Range Rovers being assembled? (The chassis numbers on these unique Rovers were: 357XXXXXX Right hand drive CKD, 359 XXXXXX Left hand drive CK.)

In later years, it was common practice to import into Costa Rica side frame assemblies from post 1982 Range Rovers, plus all four doors from Britain, and convert two-door vehicles to four-door vehicles, making them more valuable in their territory.

FLM Panel Craft, Wood and Pickett, as well as several other Coachwork Companies in London, renowned for quality conversions on vehicles such as the Austin-Morris Mini and P6 Rover into Estate cars, could see the market need for a four-door Range Rover. They could also see the need for making the Range Rover into a more luxurious vehicle. There was considerable interest from the Middle East, who could see the potential of these vehicles, whose options seemed to be limited only by the owners imagination. Lack of funds initially from BL and then Jaguar Rover Triumph prevented Rover Cars from tooling up to build their own four-door vehicles for some time.

As a stop-gap measure, Monteverdi Coach Works in Switzerland were sent two-door Range Rovers to be converted to four-door versions. Can you imagine two-door vehicles being driven from England to Switzerland and a four-door vehicle being driven back to England on the return journey, repainted in BMW colours of the day? I was lucky enough to drive one of these Swiss Monteverdi’s when it was about three-years-old. The quality of the finish was quite remarkable, though its performance was not! Land Rover was tooling up at this time to build their own four-door vehicles.

Solihull produced Range Rovers continue to evolve, becoming more and more luxurious as the motoring public’s desires change. The vehicle has gone way beyond Spen King’s 1966 vision of a working and family vehicle. And thus, we wish Range Rover a happy 50th birthday and hope that it’s production and motoring adventures may continue long into the future.

[Many thanks to James Taylor, Roverphile, UK, and Vidar Eriksen: www.range-rover-classic.com.]