Woodson Kidder Woods III (1932-2020) truly lived above and beyond.

During his 88 years, much of it spent in Hawaii, “Woody” Woods became an avid off-roader, hunter, hotelier, adventurer, pilot, sailor, film instructor, painter and benefactor. One contemporary admirer observed, “If one were writing fiction, he would have been Hollywood’s version of a leading man: tall, lean, handsome, charming, a rare individual. I wondered, ‘How could this guy be real?’”

His Land Rovers provided the vehicles to meet his interests, businesses and lust for adventure. His son, Chris Woods, said his father genuinely enjoyed his Land Rovers, right up through his ’95 NAS Defender. That Defender now resides under Chris’ stewardship.

Born in St. Louis, Woody first came to Hawaii in 1954, as a Morse Code specialist with the U.S. Navy. After his service, he returned to Missouri for a short time to run the family farm. Woody found his time in Hawaii spell-binding and in 1957, he returned to the “Big Island” of Hawai’i to instigate an extraordinary life.

The topography and grandeur of the “Big Island” would incite Woody’s ambition and creativity. The largest island in the USA (4,000 sq. miles) features 8 of the 13 climate zones in the world — from tropical to polar — and Woody’s tours would drive visitors through each of them. The island has the world’s highest sea mountain, Mauna Kea, at 32,000 feet (13,796 above sea level), Mauna Loa, the world’s most massive mountain that covers half the island, and an active group of volcanoes. In between lie deserts, temperate rain forests and dry steppes. The varied terrain inspired Woody to create opportunities to share the awe-inspiring landscape with the world.

They led Woody to purchase a Land Rover from an International Harvester dealer in Honolulu, Oahu. The Land Rover went to work on his new, 360-acre ranch at Pa’auilo. Maggie Woods, his wife of 30 years, remembers the Land Rovers on their ranch; she focused on their horses while Woody took care of the cattle. Maggie recalls, “He even took a V8 engine and installed it in an 88” Land Rover so it could climb and go faster.”

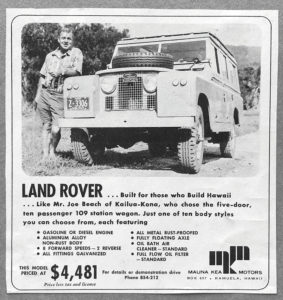

The remote nature of the ranch confronted Woody with the need to effect maintenance and repairs. How best to get parts and future models? He contacted the Rover Car Company and in 1965, and secured the Land Rover and Rover Car distributorship for the islands. He then established Mauna Kea Motors, the state’s first dealership, in a ramshackle former service station. In 1968, he expanded Mauna Kea Motors into a new, 7,000 square foot building.

His friend, Pete Hendricks, said, “Rovers proliferated on the island because of Woody. There are still many here, in daily use or ready for a rebuild.”

Maggie Woods met Woody soon after she graduated from high school in Hawaii. She cited Woody’s fascination with and admiration of Ernest Hemingway, his lifestyle and connections with hunting, fishing, exploration and adventure. Woody had started the Royal Hawaiian Air Service (“Wherever a bird could go”) and Maggie became an early employee of the company in 1965. Flying between short airstrips enabled potential visitors to reach the Big Island easier, and connected the more remote corners to the other islands.

In the early 1960s, Woody worked on land use planning for what became Laurence Rockefeller’s famous Mauna Kea Beach Hotel, which included a “hunting club,” for which nearby ranch “paniolo” (cowboys) served as guides. In turn, Woody created Hawaii Trails, a company that took you off-road, 11,000 feet up the side of Mauna Kea, in Land Rover Series IIA’s and Series III’s. A brochure explained that the Land Rover would be fully kitted-out with “first aid kit, seat belts [!], 2-way citizens band radio, fire extinguishers, hydraulic jack, heavy duty manual jack, complete set of tools, capstan winch, tow cable and rope, an axe and a shovel.” (And in some instances, a loaded rifle.) The adventures took from 1-2 days, with distances between 60-190 miles. If you wished to hunt, Woody could accommodate you on his ranch and in the mountains, with its wild pigs, goats and mountain sheep. Bird hunters would enjoy the challenge of Chinese ringneck and Japanese blue pheasant, quail, dove and partridges.

Neither Maggie nor Chris Woods ever quite knew how Woody gained the approval of private land owners, such as the Bishop Estate, to permit Woody’s businesses access to their lands; indeed, he built an 1,100 square-foot hunting lodge, 2,400 ft up the side of Mauna Kea ($30/night), so Hawaii Trails could add to its gun or bow-hunting options ($15/day for wild turkey, $50 for Mauna Kea Sheep).

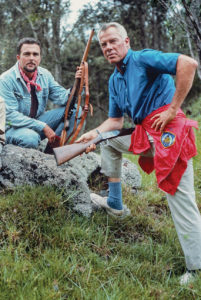

Maggie observed that Woody “loved the press” and he garnered national attention. Articles about Woody and his Land Rover-based ventures appeared in general interest magazines such as Sunset, hunting publications like Guns & Ammo, and travel magazines such as Pacific Travel News (“Land Rover Safaris on Hawaii’s Big Island,” was the headline for one article.) The American Sportsman television show ran for five years on the ABC network; one episode featured Western actors Dale Robertson and Edgar “Buck” Buchanan hunting with Woody and Hawaii Trails.

A Hawaiian Trails’ Land Rover took a reporter from the New York Times up the side of Hualalai, an 8,000 foot dormant volcano upon which Woody had built a small cabin near the summit. The reporter spent hours inside the Land Rover as it “clambered and bounced” past 6,000 feet. The cabin was “small, filled with books, bunks and a stove, and perched on the edge of a ravine; the remnants of a volcanic crater.”

Sports Illustrated ran a feature, “A Shooting Lodge High on a Volcano,” covering Woody’s lodge. The photographer, Fred Lyon, San Francisco, CA, remains world-renowned for his decades of photographic accomplishments, but he vividly remembered a hunt with Woody from that assignment.

“I’m 96-years-old,” he said in a telephone interview, “And I worked a lot as a magazine photographer. Sometimes it took a great stretch to create stories that felt real, felt natural. Sometimes the stories in magazines had a thin premise. But Woody was the real thing.”

“For a tour of the ranch, he got out his bow and arrow and we went bouncing off in his Land Rover, which felt like it was right at home. Woody said, ‘Fred, there’s a wild boar hiding in that vegetation.’ I couldn’t see anything, but Woody walked towards the bramble. I heard a rustling, and Woody let loose with an arrow and managed a direct hit. Wild boars are very ugly anyway, and this one was particularly ugly, as he’d just been hit by an arrow. I retreated to the safety of the Land Rover. Woody stood his ground and fired a few more arrows. It was the damn coolest thing I’d ever seen. I really appreciated the Rover at that point as it was — along with its other attributes — a refuge for me.”

“I did a million other stories after that, but I’ve never forgotten how colorful he was!”

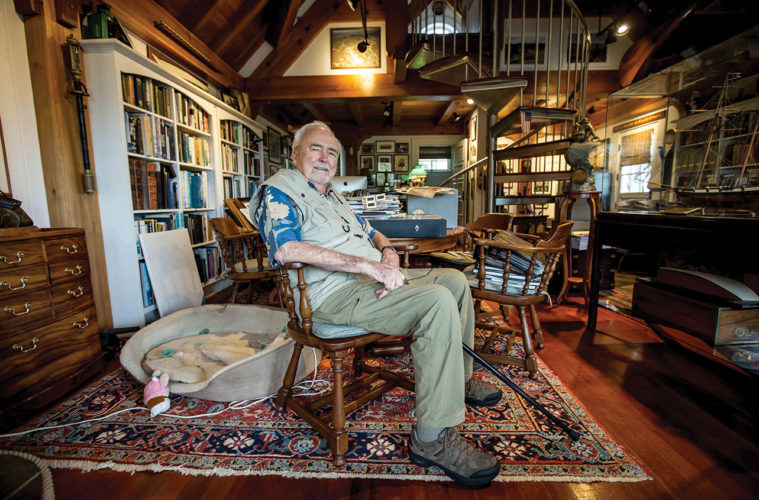

Woody also loved his life in the sky and on the sea. He created a company, Aero Meridian, to restore antique aircraft (he once owned a P-51 and a Spitfire). His deeper love in the air was for soaring, as the founder of the Mauna Kea Soaring Club, and the holder of a soaring record of 25,500 feet over Mauna Kea. He would complete nationally in the sailplane racing circuit and is considered a patriarch of the sport. He also spent considerable time on the water, navigating, racing, building and commissioning sailboats and other craft. Lastly, Woody read voraciously, dove deeply into film and became a model maker and painter.

Hannah Hind Candelario works as the Director of Advancement at the Hawai’i Preparatory Academy (HPA) in Kamuela (Waimea), Hawai‘i. Through her life growing up in Waimea and in her experience at HPA, she came to know Woody. She reflected on Woody, noting, “He did not leave one rock unturned in his lifetime, and he gave back to the community at large. When you spoke with him on the phone, you thought he was 30-years-old, not in his 80s. His sense of humor was loaded with intellect and curiosity. He had a different connection with each of his children — sailing, art, history, film, photography, flight — which reflected the breadth of his own interests. When he spoke with you, he always made you feel special. When he talked, you listened, but when you talked, he listened.”

He ran “school safaris” for students, taught a film program, and inspired the rebuilding of a pinnace sailboat named the “Imi Loa”, which he donated to HPA to revive their sailing program. Most significantly, in his time as trustee at HPA, he gifted his Waimea Village Inn to the academy; its building now constitutes their K-8 Village Campus. Around the same time, he also established the Woodson K. Woods IV Scholarship Fund, to honor his eldest son who died tragically at the age of 14, in a traffic accident. Many outstanding and grateful HPA students have benefited from this generous memorial fund.

Right to the end, Woody remained a Land Rover enthusiast. Chris Woods noted that his father would call routinely with the publication of Rovers Magazine, demanding to know if Chris had received his yet and, if so, read it through and through.

Perhaps Fred Lyon summed Woody’s life up best. “In my photography work, I had a lot of contact with movie personalities, but Woody made the myths come true. It was a photographer’s dream to find a person with both the resources and the will to make this happen. Woody had such drive and total confidence that, whatever he dreamed of, he could accomplish it.”